Dry Eye Disease

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common issue that affects hundreds of millions of people worldwide, making it one of the top reasons for visits to eye care practitioners.1 Depending on location in the world, its prevalence can be anywhere from 8.7% to 64%.2

For some, dry eye is just an occasional annoyance. But for others, moderate to severe DED can bring significant pain, make daily activities tough, lower energy levels, impact overall health, and even lead to depression. Quality of life (QoL) is influenced by various factors, especially when it comes to mental health and its social and economic repercussions. Interestingly, when it comes to vision-related QoL, DED has quite an impact, showing similar or even greater effects compared to conditions like macular degeneration, glaucoma, retinal detachment, and allergic conjunctivitis.3 Research has found an interesting connection between DED and feelings of depression, anxiety, and mood swings.4 One of the main reasons behind this is that many patients dealing with DED aren’t aware that there’s help available, so they don’t go looking for treatment. Recent studies even suggest that not getting diagnosed is associated with worse mental health-related quality of life for those with severe DED.3

If severe dry eyes are left untreated, it can cause serious problems such as eye infections, inflammation, corneal abrasions, corneal ulcers, and even vision loss. So, it’s crucial for patients to address the symptoms early and seek appropriate treatment.

In 2017, the TFOS Dry Eye Workshop updated the definition of dry eye:

Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles 5

For more details on DEWS II, click here.

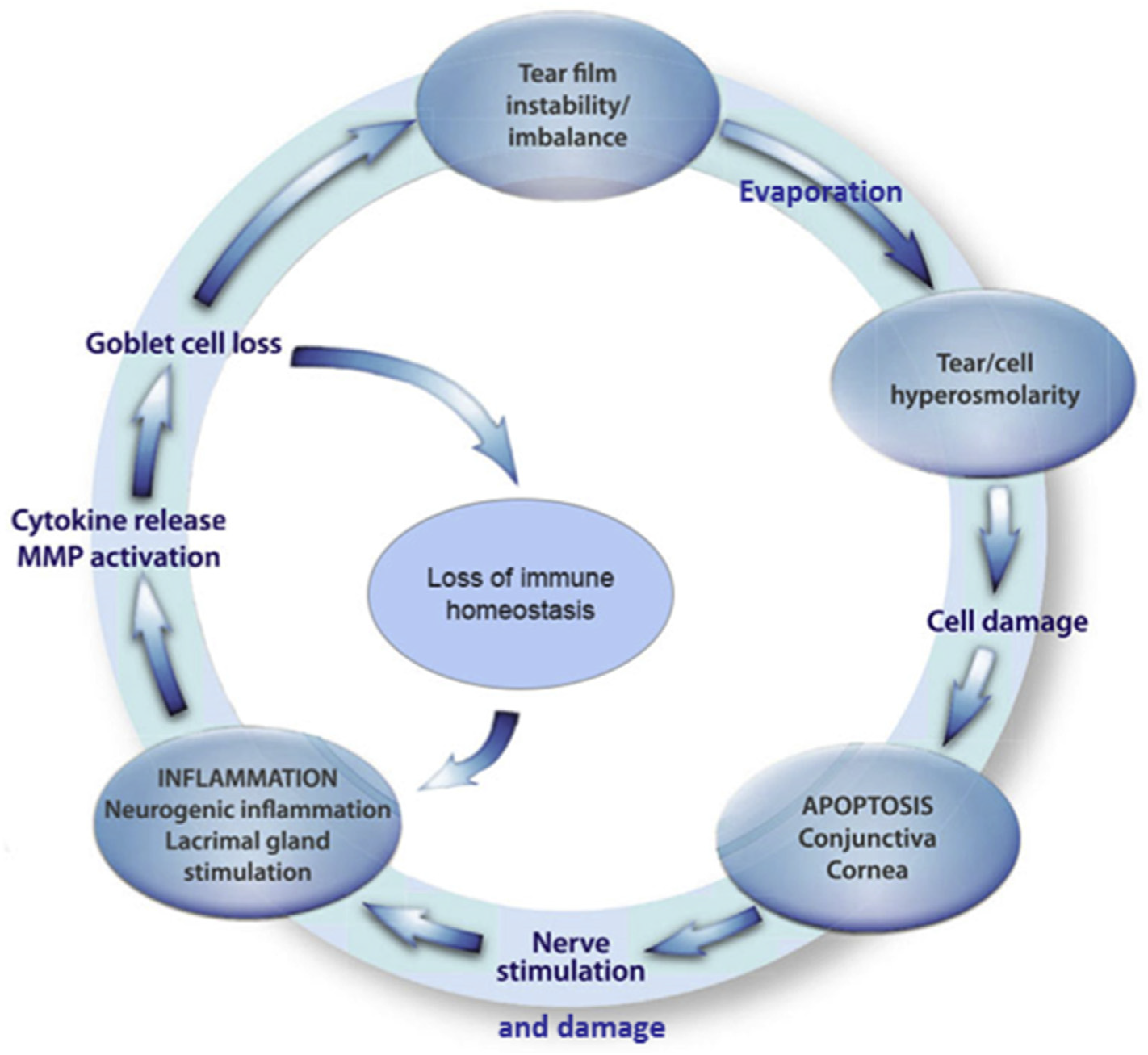

The result of this is that now dry eye is seen as a multifaceted disease of the ocular surface that happens when the tear film loses its balance. The condition comes with various eye symptoms and involves tear film instability, high tear film saltiness/ hyperosmolarity, inflammation and damage to the eye surface, and issues with eye nerve sensations. This is often referred to as the self-perpetuating vicious cycle of DED.6

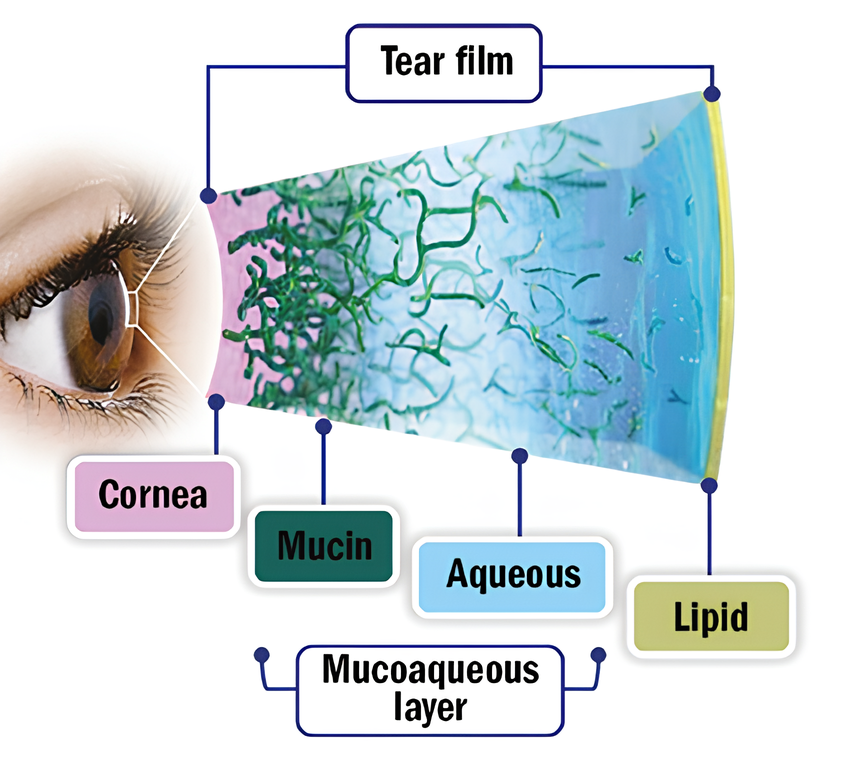

To really grasp the mechanisms behind dry eye disease, it’s key to understand the tear film’s structure and function. The tear film is a complex layer that covers the eye’s surface. It plays several crucial roles: protecting, nourishing, and lubricating the eye, as well as forming the first refractive surface of the visual system. Although it’s a bit of an oversimplification, the tear film is still often described using the classic three-layer model. However, more recently, it is encouraged to think of it as more of a mucoaqueous continuum. This means there’s a higher concentration of mucins closer to the eye’s surface and more aqueous fluid moving towards the lipid layer.7 Traditionally, the function of the different layers are as follows:

- The innermost mucin layer helps the tears stick to the surface of the eye.

- The middle aqueous layer keeps the eye nourished and protected.

- The outermost lipid layer keeps everything lubricated and stops the tears from evaporating.

DED is split into two main types: aqueous deficient dry eye (ADDE) and evaporative dry eye (EDE), with EDE being the most common. It is important to keep in mind that these types often overlap and can occur together. In fact, around 80% of all DED cases are a mix of both.1

Clinical Evaluation

Risk Factors

Risk Factors for Dry Eye as reported in the TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report are as follows:8

Consistent | Probable | Inconclusive | |

Non- | Aging

| Diabetes | Hispanic ethnicity |

Modifiable | Androgen deficiency | Low fatty acids intake | Smoking |

DED is a complex condition with many contributing factors, making it tricky to diagnose and manage. Understanding patients, including their eye health history and lifestyle, helps manage DED more effectively.9 DED usually arises from a mix of factors which can include:

Hormonal dry eye: Androgens play a crucial role in regulating the lipid and aqueous layers of the tear film.10 Low androgen levels have consistently been linked to the development of DED10

Paediatric dry eye: One study found that dry eye in children is linked to using visual display units and smartphones, with 11.03% of children affected by DED.11 This is thought to be due to a reduced blink rate and an increase in conditions like blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction, making dry eye worse

Diabetes and dry eye: Diabetes impacts the blood supply to the lacrimal gland, leading to less moisture release. It also reduces corneal sensitivity. This means that the eye can’t detect dryness and properly regulate tears, resulting in dry eye. The better a patient’s diabetes is controlled, the less severe their dry eye tends to be12

Cosmetics and dry eye: Using eye cosmetics can lead to corneal nerve irritation, make the tear film hyperosmolar, cause meibomian gland dysfunction, and make the tear film unstable. This, in turn, can lead to dry eye symptoms as the makeup migrates onto the surface of the eye13

Medications and Dry eye: Medications play a big role in causing dry eye, specifically iatrogenic dry eye (which is when medical treatment itself causes the problem). Click here to find out which medications can lead to DED

Refractive surgery and dry eye: Surgical manipulation of the cornea can disrupt the balance of the corneal nerve plexus (Eye Centre of Texas, 2022), leading to temporary dysfunction of the lacrimal functioning unit (LFU)

Cataract surgery and dry eye: Cataract surgery often leads to DED due to corneal nerve injury but also damage from the toxic components in eye drops. In fact, 100% of patients have shown abnormal tear break-up time (TBUT) and DED symptoms 12 weeks after surgery14

Signs

Signs of dry eye include can include the following 15

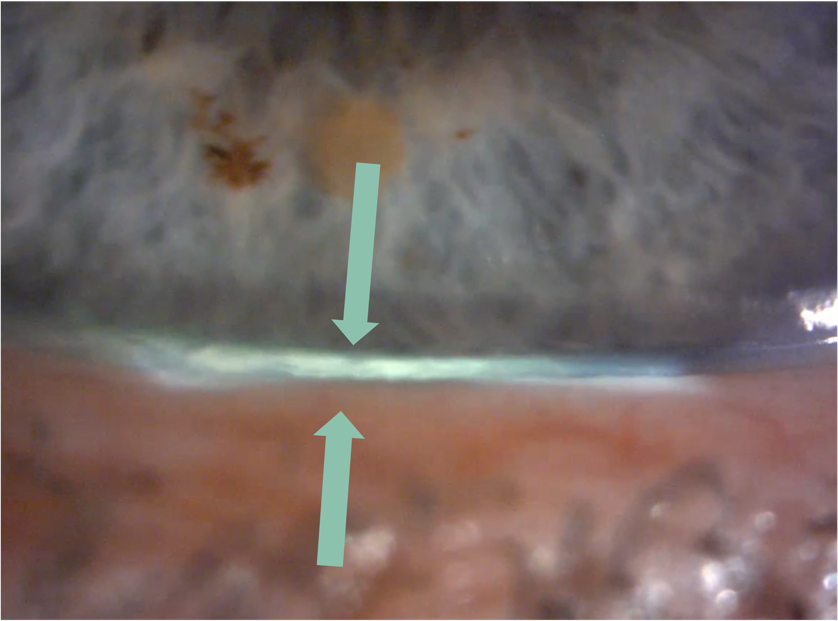

- Reduced tear meniscus at inferior lid margin (following the instillation of fluorescein, normal meniscus is not less than 0.2 mm in height)

- Raised tear osmolarity (308 mOsm/l is the most sensitive threshold to distinguish normal from mild/moderate DED, while 315 mOsm/l is the most specific cut-off)

- NITBUT (Non-invasive tear break up time) approx. <15 seconds

- Fluorescein break-up time (FBUT) <10 seconds

- Schirmer test (without anaesthesia) ≤ 5mm in 5 minutes; may be helpful in the diagnosis of Sjögren’s Syndrome, but of limited value in non-Sjögren’s DED

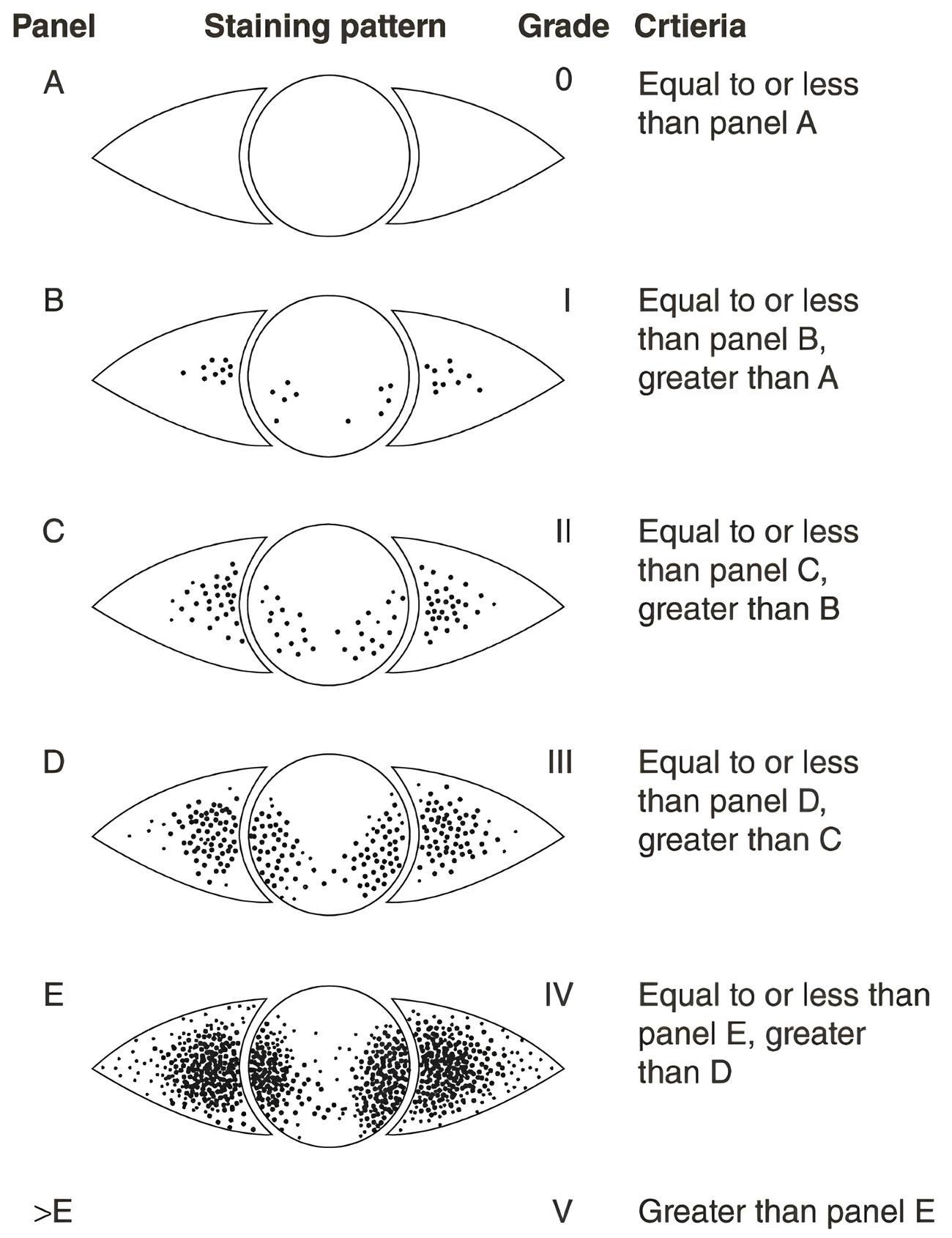

- Punctate epithelial erosions in exposed area of cornea and bulbar conjunctiva (especially in inferior third of palpebral aperture). Stain with vital dye(s) as available. Various grading systems are available (e.g. Oxford staining score)

- Lid wiper epitheliopathy

- Increased mucus strands and other tear film debris

- Filaments (adherent comma-shaped mucus strands)

- Mucus plaques

- Dellen

- Thinning and (very rarely) perforation

- Reduced corneal sensitivity

Symptoms

Symptoms of DED can include the following:

- Foreign body sensation

- Itching/irritation

- Tearing

- Redness

- Blurring/Fluctuation of vision

- Usually, bilateral

- Contact lens intolerance

- Excess tearing/watery eyes

The OSDI Questionnaire is commonly used as a way to assess patient symptom severity in clinic.

Research has shown that there isn’t a straightforward connection between the signs and symptoms of DED.16 For instance, Nichols et al., in a 2004 study examining the relationship between signs and symptoms in dry eye patients, concluded that “these findings suggest a weak connection between dry eye assessments and symptoms, posing a challenge in both clinical research and practice”.

While it’s true that the relationship between signs and symptoms isn’t always straightforward in cases of DED, it’s crucial to understand that this doesn’t diminish the significance of assessing both aspects in the clinical settings. Signs and symptoms offer valuable insights that complement each other, and it’s vital to weigh them together for an accurate diagnosis and effective management of DED. In these situations, differential diagnosis should also be considered including anterior blepharitis; allergic and infective conjunctivitis; eyelid abnormality or dysfunction leading to exposure (exposure keratopathy); nocturnal lagophthalmos (failure to close eyes at night).15

The diverse ways in which signs and symptoms present in different individuals highlight the complexity of DED. This underscores the importance of tailoring diagnostic and management approaches to each person’s unique needs and experiences.

Management & Advice

The 2017 DEWS II developed a management strategy tailored to address the needs of individuals suffering from dry eye. One of their key insights was the principle of “diagnosis precedes therapy,” emphasising the importance of identifying the specific type of dry eye (whether it’s ADDE or EDE) before initiating any management.

However, it’s crucial to understand that dry eye is unique to each patient. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution or magic drop that works for everyone. That’s why it’s essential to closely assess the patient, identify any factors that might be exacerbating their dry eye, and tailor the management plan accordingly.

Key factors from the experts17

- A REGIMEN comprising lubricants, lid hygiene, and the application of heat to the eyes for the treatment of dry eye disease and associated eye conditions.

- PRESERVATIVE FREE eye drops have shown greater effectiveness than preserved drops in decreasing inflammation on the ocular surface and increasing the antioxidant contents in tears of patients with DED”.

- DIET -There is an increasing interest in the use of nutritional supplementation or dietary modification regarded EFAs (Essential Fatty Acids) on the prevention and treatment of dry eye.

DEWS II offers a guide on how to handle patients dealing with dry eye.18 This is not as a strict rulebook but more like a toolbox filled with different strategies. It is encouraged to pick and choose what works best for each patient, mixing and matching from the various steps based on their unique condition. A summary of these step-by-step guidelines is as follows:

Step 1:

- Education is paramount for the patient. Therefore, it is key to explain the diagnosis the management, treatment, and prognosis. Making patients fully aware of the risk factors that are making them susceptible to the DED in the first place, henceforth modifying their local environment (e.g. VDU usage), education around dietary requirements, identifying, and possibly modifying systemic and topical medication.

- Lid hygiene and warm compresses

- Ocular lubricants of various types

Step 2 (if the above is insufficient)

- Non-preserved ocular lubricants due to preservative toxicity

- Tear tree oil treatment for Demodex (if present)

- Tear conservation: punctal occlusion, moisture chamber spectacles/goggled.

- Overnight treatments – such as ointment or moisture chamber devices

- In-office, physical heating and expression of the meibomian glands

- In-office intense pulsed light therapy for MGD

- Prescription drugs to manage DED

- Topical antibiotic or antibiotic/steroid combination applied to the lid margin for blepharitis (if present)

- Topical corticosteroid (limited duration)

- Topical secretagogues

- Topical non-glucocorticoid immunomodulatory drugs (such as cyclosporine)

- Topical LFA-1 antagonist drugs (such as lifitegrast)

- Oral macrolide of tetracycline antibiotics

Step 3 (if the above is insufficient)

- Oral secretagogues

- Autologous/allogeneic serum eye drops

- Therapeutic contact lens options

- Soft bandage lenses

- Rigid scleral lenses

Step 4 (if the above is insufficient)

- Topical corticosteroid for longer duration

- Amniotic membrane grafts

- Surgical punctal occlusion

- Other surgical approaches (tarsorrhaphy, salivary gland transplantation)

This article serves as an overview of the condition and treatment options. It does not serve as a clinical guidance. Eyecare provider guidelines should be used when managing patients.