When cataract surgery goes wrong

Patient presentation:

Cataract surgery is the most frequently performed elective surgical procedure globally (Table 1)1,2,3. Although serious complications are rare, they may impact significantly on visual outcome and quality of life.

Here we discuss a patient (aged 61) referred to Royal Bournemouth Hospital following complicated right cataract surgery elsewhere, exploring what went wrong during the primary surgery, her subsequent management with secondary lens implantation and iris reconstruction and finally, the leaning points from this case.

Table 1: UK Cataract Statistics1,2,3

Primary surgery and complication

The patient presented to the original cataract surgery provider for consideration for cataract surgery. Preoperative assessment had revealed dense cataracts bilaterally, cornea guttata and limited fundal view. No pseudoexfoliation was noted. Preoperative corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) was 6/120 OD (6/60 with pinhole), 6/60 OS (6/24 with pinhole). Past ocular history included myopia with an axial length of 25.64mm OD and 25.67mm OS. There was no history of previous ocular surgery, trauma or laser refractive procedures. Her medical history included asthma, atopic dermatitis and Factor V Leiden genotype. Her regular medications included Beclometasone and salbutamol inhalers, but no current or previous use of alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists.

Delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery was offered, with the plan for the right eye first. The increased risk for postoperative endothelial decompensation was discussed as well as a guarded prognosis in relation to the limited fundal view. Warning was given of post operative anisometropia and priority listing for second eye if symptomatic. She had been anxious about the cataract surgery and advised to see her general practitioner for an oral sedative to take ahead of her surgery.

There were complications during primary cataract surgery, resulting in iris damage. According to the operative records, the initial steps of the surgery were uncomplicated, with a temporal clear corneal incision at 180° and a single paracentesis at 11 o’clock. The capsulorhexis was preformed with the assistance of trypan blue visualisation. A soft-shell technique with dispersive and cohesive viscoelastic was employed to protect the corneal endothelium. However, during the sculpting stage of phacoemulsification, the pupil became smaller and the iris prolapsed from the main wound. Half of the lens was removed but then the surgeon stopped to reassess. The patient was experiencing discomfort and so a sub-Tenon’s anaesthetic of lidocaine was administered. A 10-0 nylon suture was placed in the temporal incision and the surgeon created a new incision superiorly, allowing the remainder of the cataract to be removed. During the surgery, the iris sustained trauma from the phacoemulsification tip. The surgeon elected not to insert an intra-ocular lens (IOL). The wounds were hydrated, intracameral cefuroxime and acetylcholine were administered, with the plan for a secondary IOL implantation into the intact capsular bag in four weeks. G. chloramphenicol 0.5% and g. dexamethasone 0.1% were prescribed 4x/day for four and two weeks respectively.

One week post operatively, unaided distance visual acuity (UDVA) was count fingers OD (6/48 with pinhole), with an intraocular pressure of 10mmHg. The cornea was clear, with a normal macula on optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Second opinion before onward referral

Two weeks later, she was reviewed by a vitreoretinal surgeon at the original provider and was listed for a secondary lens implantation and possible pupilloplasty. At this visit it was documented that the eye was non-inflamed, with no corneal or capsular bag compromise. While waiting for the second surgery, she developed pain and photophobia OD. This occurred four days after stopping g. dexamethasone. It appears the original postoperative instructions were for g. dexamethasone 4x/day for two weeks and g. chloramphenicol 4x/day for four weeks, perhaps representing a transcription or dispensing error. The examination at this review revealed significant postoperative anterior uveitis with cells 3+, flare 1+, keratic precipitates and fibrin plaque adhesion to the iris. There was limited fundal view due to the marked anterior segment inflammation. Macular OCT showed postoperative cystoid macular oedema with one intraretinal cyst. She was restarted on g. dexamethasone 0.1% 6x/day with a planned review in three days and surgery planned for one week. Three days later, the postoperative uveitis was resolving well and the eye was more comfortable. Cystoid macular oedema was still present. G. dexamethasone was reduced to 4x/daily with advice to continue until surgery. It was documented that she was becoming increasingly anxious about her upcoming surgery.

Unfortunately, the secondary operation had to be abandoned after the initial draping as it was felt impossible to safely perform the surgery under local anaesthetic due to extreme patient anxiety. The decision was made that it would be in the patient’s best interests to have the secondary surgery under a general anaesthetic. She was started on acetazolamide 250mg 2x/day for two days, g. bromfenac 0.9mg/ml 2x/day for two weeks and g. prednisolone 1% 4x/day for four weeks. She was referred to the Royal Bournemouth Hospital as the original provider did not have the facilities to offer general anaesthesia.

Diagnosis and Management: Third opinion and corrective surgery

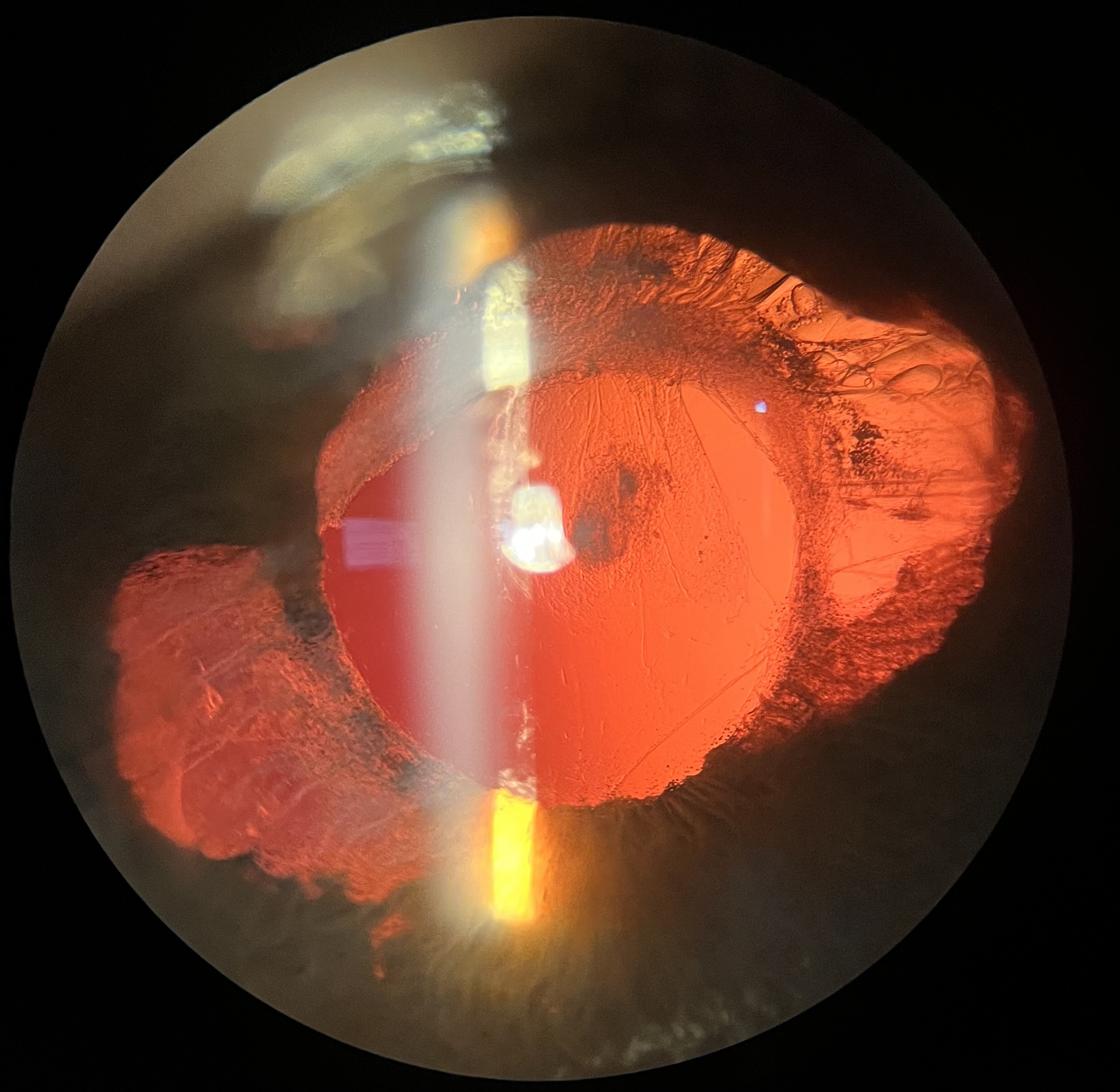

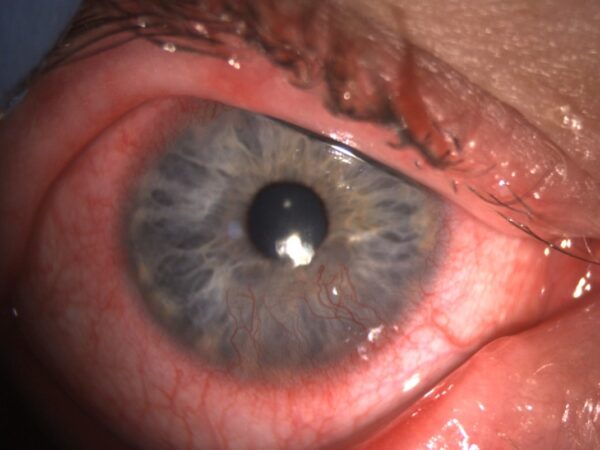

On initial assessment at the Royal Bournemouth Hospital, the right eye was aphakic with an anterior capsular platform present and an intact posterior capsule. The anterior and posterior capsule was fully fused. There were signs of significant iris trauma with nearly 360 degrees of iridocapsular adhesion and widespread areas of iris tissue loss, as shown in Figure 1. She had a clear cornea, a suture in the temporal incision, a deep and quiet anterior chamber and normal macula and fundus. Time was taken during this consultation to talk to the patient and help her understand what had happened, why the complication had occurred and what corrective steps were possible.

She was listed for surgery with planned synechiolysis, capsular exploration, sulcus intraocular lens implantation and iris reconstruction under general anaesthetic. She was advised to remain on topical steroids 3x/day until the surgery.

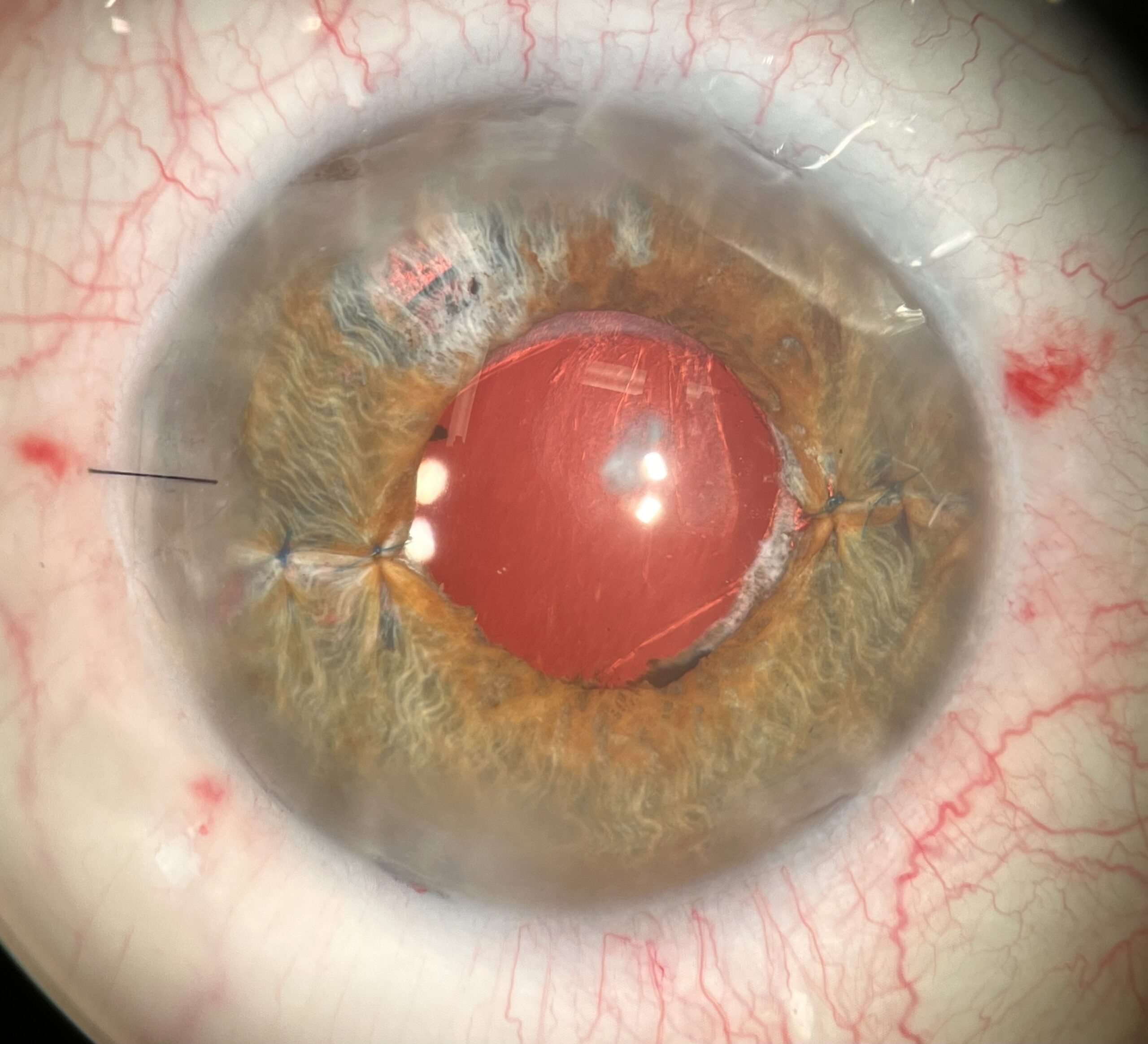

The surgical repair was performed under general anaesthetic. The original suture was removed, then the iridocapsular adhesions were divided with scissors and viscoelastic to reform the sulcus. An attempt to reopen the capsular bag was made, but the anterior and posterior capsule was firmly fused. A 3-piece +13.0D Tecnis ZA9003 intraocular lens (Johnson and Johnson Vision) was placed in the sulcus. Intracameral acetylcholine was administered and a 10/0 nylon suture placed in the main port. The two large iris defects were repaired with four 10/0 prolene sutures using sliding Siepser knots. Viscoelastic was removed, wounds hydrated and intracameral cefuroxime and subconjunctival dexamethasone were administered.

Follow up

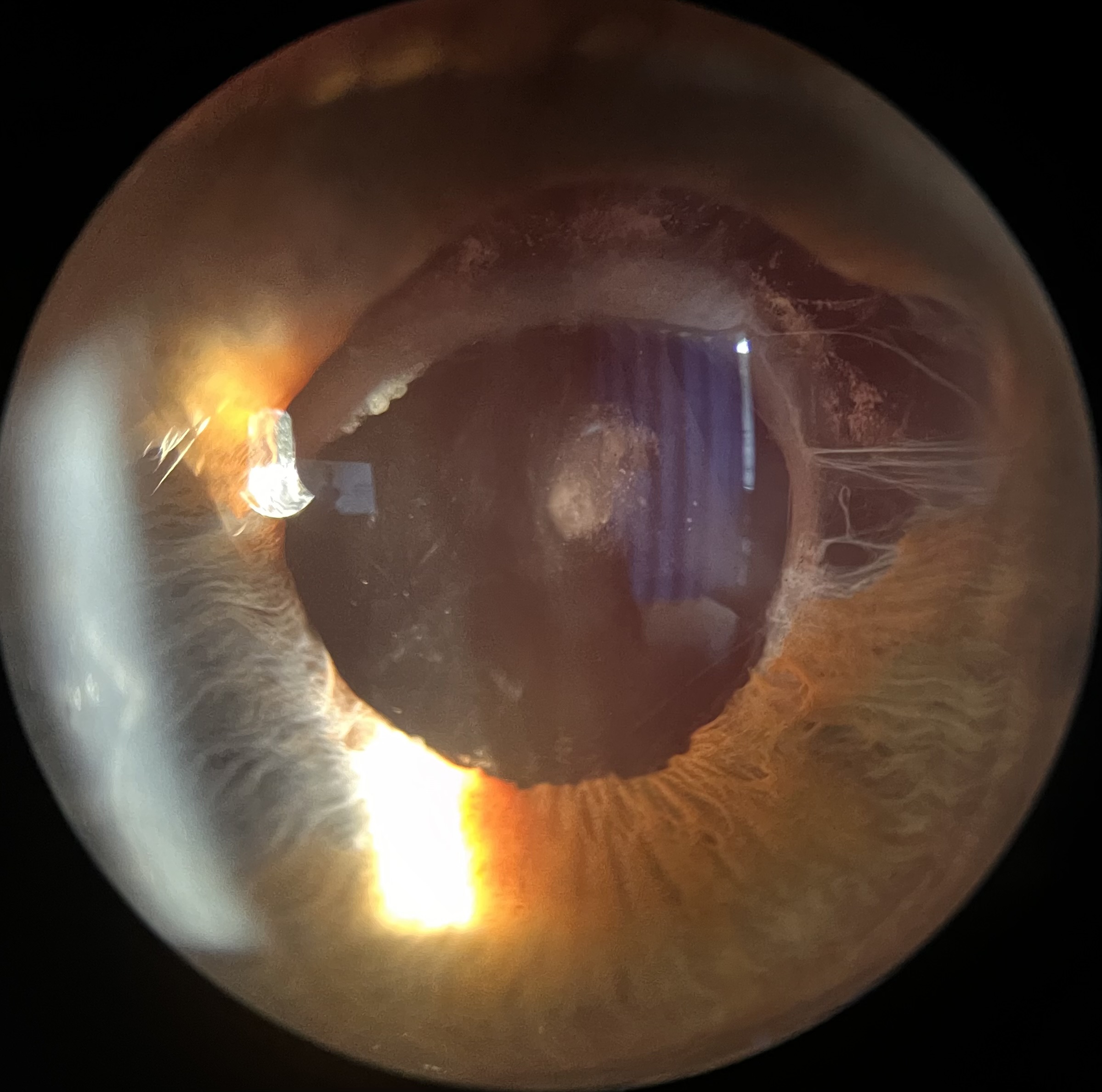

The result at one week postoperatively is shown in Figure 2, demonstrating a round pupil with significant reduction of transillumination defects. UDVA was 6/9 OD with a plano refractive outcome. Early posterior capsule opacification (PCO) was present and a YAG posterior capsulotomy was performed three months later with improvement in UDVA to 6/7.5. The patient was delighted and relieved with the postoperative outcome, with no photophobia and excellent quality of vision. She was happy to proceed with cataract surgery to her fellow eye, which has now been completed without complication.

Conclusions

This case offers helpful learning opportunities to reflect on the mechanism of iris trauma during cataract surgery, factors increasing risk, how to avoid iris trauma and how to manage trauma when it occurs. Table 2 provides an overview of the main themes and considerations that will be discussed here.

Iris trauma during cataract surgery

Factors increasing risk of iris trauma

There are a number of factors that increase the risk of iris trauma during cataract surgery. These can be divided into 1) those relating to the eye and, 2) patient-related factors. Factors relating to the eye include poor surgical field of view due to corneal pathology or scarring, dense or intumescent white cataract with poor or no red reflex, a small poorly dilating pupil, intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, previous ocular trauma or pseudoexfoliation with weak zonules and unstable capsular bag, previous ocular surgery, previous ocular inflammatory conditions such as anterior uveitis, and iatrogenic factors such as alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists (e.g. tamsulosin) and topical glaucoma medications 4,5. Patient factors include poorly managed anxiety, dementia, hearing impairment, reduced cooperation, uncontrolled movement, neck or back injuries that prevent optimal positioning for the surgery, large body habitus and respiratory conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease4,5.

Our patient presented with a number of risk factors that had made the primary cataract surgery more technically challenging, including a dense cataract, poor red reflex, intraoperative floppy iris and cornea guttata. This patient was also anxious about the procedure and had her surgery on a high-volume list, with limited time for counselling by the surgical team on the day of surgery, and no availability of intravenous sedation.

How to avoid iris trauma

A thorough preoperative assessment is imperative. This was done for the patient as part of the primary surgery and included a detailed past ocular and medical history and ophthalmic examination. Based on this, a soft-shell technique and capsulorhexis with trypan blue was planned for the primary surgery.

Possible ways in which iris trauma may occur include during iris manipulation, mechanical iris stretching, pupil dilation with iris retractor hooks or pupil expansion rings, from the phacoemulsification tip, from iris prolapse out of the wounds, during aspiration of the cortex with the irrigation/aspiration probe and during implantation of the IOL4. Several of these factors applied to our patient. An important learning point here is that each step of cataract surgery is reliant on how well the previous step of the surgery has been performed. Ensuring that each step is done to the optimal level is key in minimising the risk of intraoperative complications. Different approaches for managing poorly dilating pupils and eyes in which we anticipate intraoperative floppy iris syndrome include intraoperative mydriatic agents such as phenylephrine, mechanical iris stretching, and pupil stabilisation with iris retractors or pupil expansion rings6. A step-wise approach for managing small pupils is of benefit6. Great care also needs to be taken to avoid trauma from the phacoemulsification tip when the iris is unstable, as unfortunately happened in this case.

Patient factors such as anxiety are equally important. Careful consideration should be given to the choice of local anaesthetic, and whether oral or IV sedation, or general anaesthesia are in the patient’s best interests to ensure the surgery can be performed safely (NICE guidance, 2017)7.

Managing iris trauma

If iris trauma has occurred, it is helpful to reassess and plan for the safest way to complete the surgery and leave the eye in the best state possible. The aetiology of iris trauma will dictate the next surgical steps. It is essential to check how the patient is, provide reassurance and add additional local anaesthetic if the surgeon anticipates that surgery will take longer than originally planned. If iris trauma has occurred in the context of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome and prolapse though the main wound, it may be worth considering placing a suture in the wound and moving to a different position to create a new main wound. This was done during the primary surgery for this patient. Other things to consider include administering intracameral mydriatics, highly cohesive viscoelastic to help push the iris more posteriorly and away from the main wound, and the use of iris retractor hooks. The option of removing the lens fragments and SLM and leaving the eye aphakic with a planned secondary surgery when then eye has settled may also be in the patient’s best interests, as was done in this case.

Meticulous post operative care is important. Unfortunately, the patient in this case was advised to stop the topical steroid just two weeks after the initial complicated surgery, leading to significant postoperative uveitis that further compromised the eye.

Options for lens implantation

There were various options for the secondary IOL implantation for this patient: 1) opening the capsular bag and implanting the IOL in the bag, 2) implanting a 3-piece IOL into the sulcus, or 3) implanting an angle-supported anterior chamber IOL (AC-IOL)8. An iris-fixated lens was not possible due to the iris trauma. The first option of opening the capsular bag was attempted, but the capsular fusion and concerns over capsule stability led to this being abandoned. Thus, the second option of implanting a 3-piece IOL into the sulcus was performed to minimise manipulation of the capsular bag and the risk of posterior capsular or zonule rupture. Option three may be considered, however AC-IOLs are associated with an increased risk of anterior chamber inflammation, corneal decompensation and secondary glaucoma. As this patient had Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, this would not have been the best option.

Morbidity of iris defects

This iris acts as a light-transmitting diaphragm that controls the size and shape of the pupil and thereby the amount of light entering the eye9. The iris also has an important role in visual acuity and the quality of vision by reducing aberrations from the lens and cornea by reducing the amount of light entering the pupil, preventing excessive glare and enhancing depth of focus. Any iris injury may impair its function and result in symptoms of glare, photophobia and decreased contrast sensitivity, as well as impaired cosmesis 9.

Management of iris defects

The management of iris defects can be divided into non-surgical and surgical options.

Non-surgical techniques

Not all iris defects require surgical correction. Topical miotic agents (e.g. pilocarpine (cholinergic muscarinic receptor agonist) and brimonidine (alpha2-adrenoceptor agonist)), may have some benefit in cases of minor pupillary damage, but are unlikely to be of benefit in cases of significant iris trauma9,10. Their success and compliance may be further hindered by unwanted side effects (topically and systemically). Prosthetic iris coloured contact lenses are another non-surgical option. The pupillary diameter and iris colour can be customized to achieve a pinhole effect to reduce glare and photophobia, as well as improve cosmesis9,11. The limitations of prosthetic iris coloured contact lenses include cost and the risks associated with contact lens wear such as ocular surface disease, corneal ulcers and contact lens intolerance.

Surgical techniques

Surgical options include prosthetic iris intraocular implants, iris suturing and corneal tattooing.

Iris prosthesis

There are several iris prostheses options, including 1) large incision, rigid diaphragm, aniridic intraocular lens style devices, 2) small-incision devices incorporating a capsular ring and 3) flexible, customised, small-incision iris prostheses12. Rigid diaphragm devices have an opaque peripheral border to mimic the iris, require a large incision (10.5mm) and are fixated in the ciliary sulcus. The limitations of these devices are that they only exist in a limited colour selection (usually black) for the peripheral opaque zone and so do not offer any cosmetic improvement 12,13. Large incisions also carry higher risks of intraoperative hypotony, suprachoroidal haemorrhage and postoperative astigmatism. In eyes with an intact capsulorhexis and good capsular support, insertion of an intracapsular iris segment can help repair iris defect. These devices consist of a capsular tension ring with black fin segments12. They can be inserted through a smaller incision of 3.5mm, however the disadvantages are that they offer no cosmetic matching and may be susceptible to fracture with over manipulation. There are newer intraocular iris prosthesis options that offer a more individualised approach to iris reconstruction. A flexible biocompatible silicone elastomer iris (such as the HumanOptics CustomFlex Artificial Iris) can be folded and injected into the eye using a small incision of 2.5-2.8mm12,13. The prosthesis can be individualised based on the specific ocular requirements and can be colour matched to the fellow eye. The main disadvantages of these are cost and availability, as well as being technically challenging to perform.

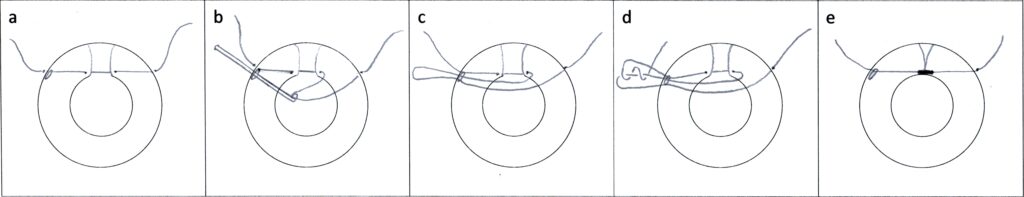

Iris suturing

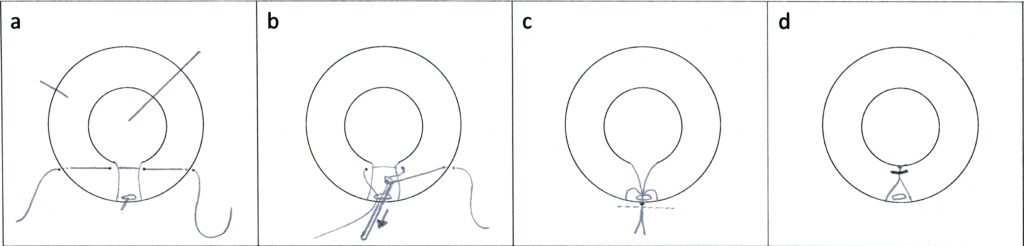

McCannel14 in 1976 first conceptualised minimally invasive pupilloplasty. His original technique allowed for iris approximation within the anterior chamber by passing a long needle via two corneal paracenteses (Figure 3). This technique was later modified by Siepser15 in 1994, using a sliding knot technique (Figure 4). Another technique is iris cerclage suture for pupilloplasty16. In our case, the two large iris defects were repaired with four 10/0 prolene Siepser knots.

In cases of significant iris trauma as seen in this patient, surgical management with pupilloplasty (although more technically challenging and requiring an experienced anterior segment surgeon) can achieve excellent results in terms of both functionality and cosmesis12.

Corneal tattooing

Although corneal tattooing does not repair the iris defect it has been used to improve the functional and cosmesis issues related to iris defects. There are different techniques in which keratopigmentation may be performed17,18,19. Keratopigmentation may improving functionality of iris defects20 but will not give the same cosmetic result as pupilloplasty or an individualised iris prosthesis. The most common complication of keratopigmentation is photophobia, and more research is needed into the long-term effects of pigments on the cornea21.

Holistic patient approach

A holistic approach to patient care is important in any clinical encounter, but particularly in patients who have had complications of surgery. It was documented that our patient was very anxious even before her primary surgery. Her planned secondary procedure was cancelled on the day as the surgeon did not feel it was possible to safely perform the secondary surgery under local anaesthetic due to patient anxiety. Our patient had an emotionally traumatic journey leading up to the eventual third opinion and reconstructive surgery, some of which could have been avoided. It is important to dedicate time during each clinic review to talk to the patient and allow them to express their fears or concerns. This helps us understand how best to approach the surgery – both from a surgical and anaesthetic perspective.

Summary and learning points

Cataract surgery is the most frequently performed elective surgical procedure globally and enjoys high success rates. While serious complications are rare, their impact and implications for the patient are significant. This case study offers helpful learning opportunities and take-home messages:

- The importance of thorough pre-operative assessment and risk stratification

- Meticulous planning, anticipation of possible problems and steps to help mitigate these

- Optimal post operative care – including appropriate postoperative prescriptions, follow-up and thorough patient counselling – to avoid the patient feeling they have been abandoned

- Recognise and manage patient anxiety appropriately both pre- and intra-operatively, considering sedation or general anaesthetic in more complex cases

- In cases of significant iris trauma, surgical management with pupilloplasty can achieve excellent results in terms of both functionality and cosmesis

Acknowledgment: We graciously acknowledge the patient’s consent for her journey and images to be shared for educational and training purposes.

References

- Day AC, Norridge CFE, Donachie PHJ, et al. Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery: report 8, cohort analysis of the relationship between intraoperative complications of cataract surgery and axial length. BMJ Open 2022;12:e053560. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053560

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Scenario: Management of cataracts in adults. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cataracts/management/adults/#cataract-surgery-adults (Accessed 7th June 2023)

- Laser Eye Surgery Hub. Cataract Statistics and Data. https://www.lasereyesurgeryhub.co.uk/data/cataract-statistics/ (Accessed 7th June 2023)

- Foster GJL, Ayres B, Fram N, Khandewal S, Ogawa GSH, MacDonald S, Miller KM, Snyder ME, Vasavada AR. Management of common iatrogenic iris defects induced by cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 47(4):p 522-532, April 2021. DOI: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000411

- Handzel DM, Briesen S, Rausch S, Kälble T. Cataract surgery in patients taking alpha-1 antagonists: know the risks, avoid the complications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012 May;109(21):379-84. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0379. Epub 2012 May 25. PMID: 22690253; PMCID: PMC3371631.

- Grzybowski A, Kanclerz P. Methods for achieving adequate pupil size in cataract surgery Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 31(1):p 33-42, January 2020. DOI: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000634

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Cataracts in adults: management 2017 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng77/chapter/recommendations#anaesthesia (Accessed 7th June 2023)

- Cheng, KKW, Tint NL, Sharp J, Alexander P. Surgical management of aphakia. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 48(12):p 1453-1461, December 2022. DOI: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000954

- Gurnani B, Kaur K. Traumatic Iris Reconstruction. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Jan- 2023. PMID: 35201728.

- Panarese V, Moshirfar M. Pilocarpine. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Dec 2022. PMID: 32310588

- Vásquez Quintero A, Pérez-Merino P, Fernández García AI, De Smet H. Smart contact lens: A promising therapeutic tool in aniridia. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed). 2021 Nov; 96 Suppl 1:68-73.

- Crawford A, Freundlich S, Zhang J, McGhee CNJ. Iris reconstruction: A perspective on the modern surgical armamentarium. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2021 Jun 28;14(2):69-73. doi: 10.4103/ojo.ojo_160_21. PMID: 34345138; PMCID: PMC8300278.

- Koch KR, Heindl LM, Cursiefen Claus, Koch HR. Artificial iris devices: Benefits, limitations, and management of complications. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 40(3):p 376-382, March 2014. | DOI: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.08.051

- McCannel MA. A retrievable suture idea for anterior uveal problems. Ophthalmic Surg. 1976;7:98–103.

- Siepser SB. The closed chamber slipping suture technique for iris repair. Ann Ophthalmol. 1994;26:71–2.

- Ogawa GS. The iris cerclage suture for permanent mydriasis: A running suture technique. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1998;29:1001–9.

- Alio JL, Rodriguez AE, Toffaha BT. Keratopigmentation (corneal tattooing) for the management of visual disabilities of the eye related to iris defects. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011; 95:1397–1401.

- Alio JL, Rodriguez AE, Toffaha BT, et al. Femtosecond-assisted keratopigmentation for functional and cosmetic restoration in essential iris atrophy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011; 37:1744–1747. 59

- Alio JL, Rodriguez AE, El Bahrawy M, et al. Keratopigmentation to change the apparent color of the human eye: a novel indication for corneal tattooing. 2016; 35:431–437.

- Alio JL, Al-Shymali O, Amesty MA, Rodriguez AE. Keratopigmentation with micronised mineral pigments: complications and outcomes in a series of 234 eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018; 102:742–747.

- Lian RR, Siepser SB, Afshari NA. Iris reconstruction suturing techniques. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 31(1):p 43-49, January 2020. DOI: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000628

Latest Articles

HCP Popup

Are you a healthcare or eye care professional?

The information contained on this website is provided exclusively for healthcare and eye care professionals and is not intended for patients.

Click ‘Yes’ below to confirm that you are a healthcare professional and agree to the terms of use.

If you select ‘No’, you will be redirected to scopeeyecare.com

This will close in 0 seconds