Understanding and Managing Contact Lens-Related Bacterial Keratitis

What is bacterial keratitis?

Bacterial keratitis (BK) is a type of infectious keratitis (also known as corneal infection) caused by bacteria. It is a painful and potentially sight-threatening condition, and a leading cause of corneal blindness worldwide.

How common is BK?

The global incidence of infectious keratitis is estimated to range from 2.5 to 799 cases per 100,000 population-year, depending on geographical and socioeconomic factors (1). In the UK, a recent study showed that infectious keratitis is reported to affect 34.7 per 100,000 population-year between 2007 to 2019 (1-3). While both bacteria and fungi are common causative organisms, BK accounts for over 90% of infectious keratitis in the UK (4-7).

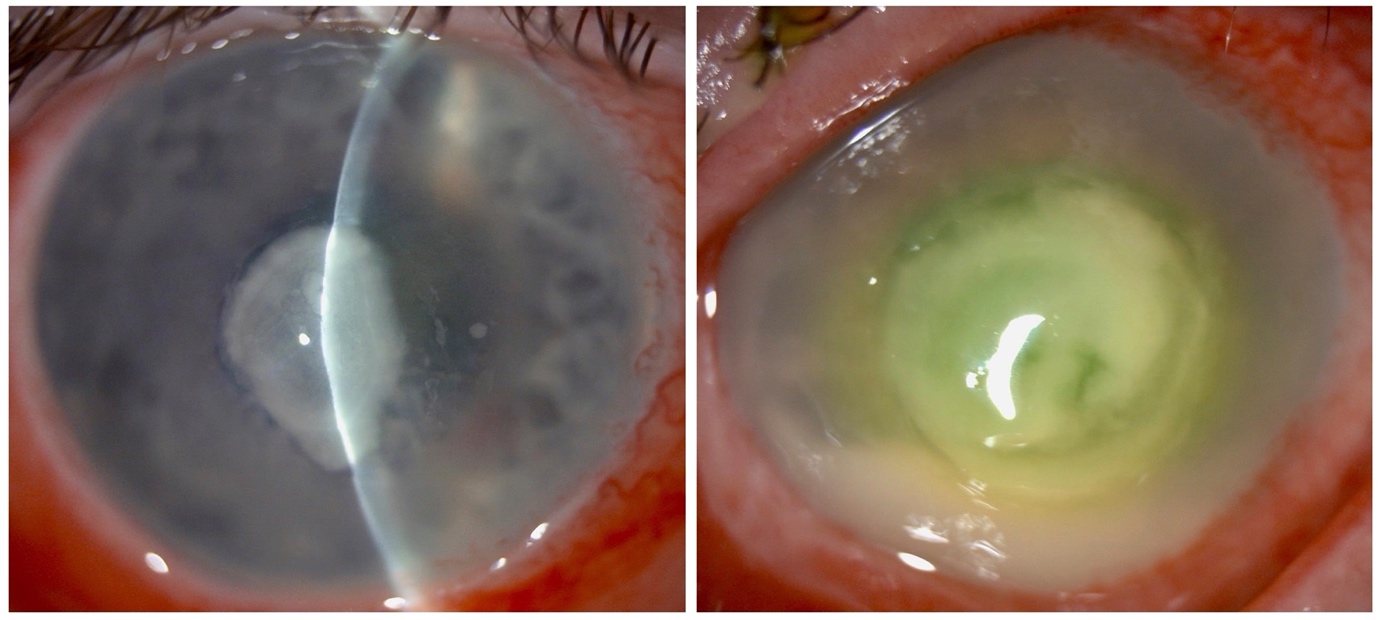

How is BK diagnosed?

Patients affected by BK often present with ocular pain, photophobia, conjunctival redness, reduced vision, and/or mucopurulent discharge (8). Slit-lamp biomicroscopic examination demonstrate a range of clinical signs, including conjunctival injection/redness, corneal epithelial defect, stromal infiltrate (or micro-abscess), stromal oedema, anterior chamber inflammation (e.g. presence of cells, flare, fibrin, and/or hypopyon), and posterior synechiae (9). Diagnosis of BK is often made on clinical grounds, with support from microbiological investigations. Corneal sampling for microscopy, culture and susceptibility (MC&S) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is useful for determining the underlying causative organisms and guiding targeted antimicrobial treatment (9,10).

What are the risk factors of CL-related BK?

BK rarely occurs without a predisposing factor, owing to the eye’s robust innate defences. Contact lens (CL) wear, ocular trauma, ocular surface diseases (including dry eye disease, neurotrophic keratopathy, limbal stem cell deficiency, etc.), are some of the most common risk factors.

Among all, CL wear has been consistently reported to be a major risk factor for BK in developed countries, including the UK, accounting for 30-40% of all BK cases (11). CL wear increases the risk of BK by 10- to 80-fold when compared with non-CL wear (12). Patients affected by CL-related BK are usually of younger, working-age adults.

Behavioural factors play an important role and are documented in over half of CLBK cases. These include overnight CL wear, use of CL during swimming or showering, prolonged daily wear exceeding 16 hours, inadequate storage case hygiene, and poor hand hygiene (13). These factors increase the risk of CL contamination by pathogens, for instance, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen well adapted to survive in CL solutions and form biofilms (11,13).

The types of CL have been shown to influence the risk of developing BK. Soft monthly disposables account for most cases, with extended-wear lenses carrying the highest intrinsic risk due to microbial retention and/or biofilm formation. In contrast, rigid gas-permeable, bandage, and cosmetic lenses are less frequently implicated. Orthokeratology lenses (Ortho-K), an increasingly common method to reduce myopic progression in children, may increase the risk of BK, though strong evidence is lacking (13,14).

What are the differential diagnoses?

Common differential diagnoses of BK include fungal keratitis, Acanthamoeba keratitis, and herpetic simplex keratitis. Fungal keratitis typically has a slower onset and is characterised by feathery-edged stromal infiltrates, satellite lesions, and often a history of vegetative ocular trauma (15). Acanthamoeba keratitis is notable for its severe, disproportionate pain relative to clinical signs and may present with ring-shaped stromal infiltrates or perineural infiltrates (16).

Herpetic simplex keratitis commonly features dendritic epithelial ulcers and reduced corneal sensitivity on examination (17). It may manifest in different forms: epithelial keratitis, which typically responds well to topical antiviral therapy and is often self-limiting; or stromal keratitis and keratouveitis, which have been linked to immune-mediated responses and require the use of topical corticosteroids and long-term systemic antiviral treatment (as prophylaxis in recurrent cases).

What is the management of CL-related BK?

Immediate cessation of CL wear is crucial in all cases with suspected BK. Patients with suspected or confirmed CL-related BK should be referred urgently within 24 hours to the local hospital eye department to ensure timely management and minimise the risk of sight loss and complications (18-20). Any used lenses, storage cases, or solutions should be retained and sent for microbiological culture and sensitivity testing (as they may be useful in some cases). Corneal sampling for microscopy, culture and susceptibility testing should be performed when clinically indicated, before commencing any antimicrobial therapy (18,21). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be considered where available to improve diagnostic yield (10). Hospital admission is recommended for severe infections, threatened perforation, or when adherence to intensive therapy is uncertain (20).

Empirical management with broad-spectrum topical antibiotics should be initiated immediately after the initial assessment and/or microbiological investigation. For small, non-central lesions (<1 mm) without sight-threatening features, topical monotherapy with 3rd or 4th generation fluoroquinolone (e.g. levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) is recommended, while severe infections often require dual fortified therapy (e.g. cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone/aminoglycoside) (22). Topical antibiotics are typically instilled hourly for the first 48 hours, then every two hours for the next 72 hours, before tapering to every 4–6 hours (for a week or longer) as the condition improves. Patients should be reviewed and monitored closely throughout the treatment period as non-responsive cases may require repeat corneal sampling/investigation and/or surgical interventions. Topical cycloplegic agents are useful in relieving ocular pain and photophobia and prevent synechiae. Topical steroids may be useful for controlling intraocular inflammation after the initial sterilisation phase (with intensive antibiotics) where acute infection is controlled and the eye shows signs of clinical improvement (23).

For asymptomatic CL wearers presenting with redness, discomfort, or visual changes, lens wear should be discontinued immediately and urgent assessment arranged. Review by a local optometrist within 24–48 hours is appropriate for non-sight-threatening concerns, with escalation to hospital services if infection is suspected.

How to reduce the risk of CL-related BK?

Preventive strategies are key to reducing the risk of CL-related BK. Strict hand hygiene, proper lens and case care/hygiene, and avoidance of water contact should be emphasised to all CL wearers (24). High-risk behaviours such as swimming, showering, or sleeping with CL wear must be avoided (25). Daily disposable CL are associated with a lower contamination risk, while silicone hydrogel CL improve oxygen permeability (26). Regular professional assessments of lens fit, corneal health, and tear film stability are advisable. Compliance with appropriate CL cleaning and wear should be emphasised. Novel approaches to storage and handling have also been explored. “Smart Touch” packaging has shown early promise in reducing contamination (27).

Tips for long-term contact lens use in children

Soft CL and Ortho-K lenses are commonly used in the management of childhood myopia (28). However, younger children may not readily recognise or report early symptoms of ocular discomfort or infection. Education of parents or carers is therefore essential to ensure safe lens use, proper hygiene, and early recognition of potential complications.

As Ortho-K involves overnight lens wear, it carries a higher risk of complications due to factors such as corneal hypoxia and mechanical stress. As a result, Ortho-K should ideally be offered only to patients/families with good compliance and have access to emergency ophthalmic care if needed (29). Where possible, daily disposable soft CL should be considered as a safer alternative for myopia control (30). Additionally, the use of daily logs or mobile apps to monitor and encourage compliance may be beneficial for parents and carers. In view of the potential risks of BK, it is advisable to consult local optometrists and/or ophthalmologists prior to the start of Ortho-K wear.

References

- Ting DSJ, Ho CS, Deshmukh R, Said DG, Dua HS. Infectious keratitis: an update on epidemiology, causative microorganisms, risk factors, and antimicrobial resistance. Eye (Lond). 2021;35(4):1084-101.

- Seal DV, Kirkness CM, Bennett HG, Peterson M, Group KS. Population-based cohort study of microbial keratitis in Scotland: incidence and features. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 1999;22(2):49-57.

- Ibrahim YW, Boase DL, Cree IA. Epidemiological characteristics, predisposing factors and microbiological profiles of infectious corneal ulcers: the Portsmouth corneal ulcer study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(10):1319-24.

- Ting DSJ, Ho CS, Cairns J, Elsahn A, Al-Aqaba M, Boswell T, et al. 12-year analysis of incidence, microbiological profiles and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of infectious keratitis: the Nottingham Infectious Keratitis Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(3):328-33.

- Tan SZ, Walkden A, Au L, Fullwood C, Hamilton A, Qamruddin A, et al. Twelve-year analysis of microbial keratitis trends at a UK tertiary hospital. Eye (Lond). 2017;31(8):1229-36.

- Ting DSJ, Settle C, Morgan SJ, Baylis O, Ghosh S. A 10-year analysis of microbiological profiles of microbial keratitis: the North East England Study. Eye (Lond). 2018;32(8):1416-7.

- Tavassoli S, Nayar G, Darcy K, Grzeda M, Luck J, Williams OM, et al. An 11-year analysis of microbial keratitis in the South West of England using brain-heart infusion broth. Eye (Lond). 2019;33(10):1619-25.

- Salmon JF. Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. 10th Edition ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2024. 968 p.

- Ting DSJ, Gopal BP, Deshmukh R, Seitzman GD, Said DG, Dua HS. Diagnostic armamentarium of infectious keratitis: A comprehensive review. Ocul Surf. 2022;23:27-39.

- Hammoudeh Y, Suresh L, Ong ZZ, Lister MM, Mohammed I, Thomas DJI, et al. Microbiological culture versus 16S/18S rRNA gene PCR-sanger sequencing for infectious keratitis: a three-arm, diagnostic cross-sectional study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1393832.

- Ting DSJ, Cairns J, Gopal BP, Ho CS, Krstic L, Elsahn A, et al. Risk Factors, Clinical Outcomes, and Prognostic Factors of Bacterial Keratitis: The Nottingham Infectious Keratitis Study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:715118.

- Dart JK, Stapleton F, Minassian D. Contact lenses and other risk factors in microbial keratitis. Lancet. 1991;338(8768):650-3.

- Suresh L, Hammoudeh Y, Ho CS, Ong ZZ, Cairns J, Gopal BP, et al. Clinical features, risk factors and outcomes of contact lens-related bacterial keratitis in Nottingham, UK: a 7-year study. Eye (Lond). 2024;38(18):3459-66.

- Sartor L, Hunter DS, Vo ML, Samarawickrama C. Benefits and risks of orthokeratology treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Ophthalmol. 2024;44(1):239.

- Ting DSJ, Galal M, Kulkarni B, Elalfy MS, Lake D, Hamada S, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Fungal Keratitis in the United Kingdom 2011-2020: A 10-Year Study. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(11).

- Azzopardi M, Chong YJ, Ng B, Recchioni A, Logeswaran A, Ting DSJ. Diagnosis of. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(16).

- Sibley D, Larkin DFP. Update on Herpes simplex keratitis management. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(12):2219-26.

- Cai Y, Clancy N, Watson M, Hay G, Angunawela R. Retrospective analysis on the outcomes of contact lens-associated keratitis in a tertiary centre: an evidence-based management protocol to optimise resource allocation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2024;109(1):21-6.

- The College of Optometrists. CL-associated infiltrative keratitis — Clinical Management Guidelines 2024 [09 Oct 2025]. 8th:[Available from: <p data-end=”651″ data-start=”517″>https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/keratitis_cl-associatedinfiltrative.

- The College of Optometrists. Microbial keratitis (bacterial, fungal) — Clinical Management Guidelines 2024 [09 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.college-optometrists.org/clinical-guidance/clinical-management-guidelines/microbialkeratitis_bacterial_fungal.

- Carnt N, Samarawickrama C, White A, Stapleton F. The diagnosis and management of contact lens-related microbial keratitis. Clin Exp Optom. 2017;100(5):482-93.

- Song A, Yang Y, Henein C, Bunce C, Qureshi R, Ting DSJ. Topical antibiotics for treating bacterial keratitis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2025;7(7):CD015350.

- Herretes S, Wang X, Reyes JM. Topical corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy for bacterial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10(10):CD005430.

- Stapleton F, Carnt N. Contact lens-related microbial keratitis: how have epidemiology and genetics helped us with pathogenesis and prophylaxis. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(2):185-93.

- Lakkis C, Lorenz KO, Mayers M. Topical Review: Contact Lens Eye Health and Safety Considerations in Government Policy Development. Optom Vis Sci. 2022;99(10):737-42.

- Prajna NV, Radhakrishnan N, Sharma S. Prevention in the Management of Infectious Keratitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142(3):241-2.

- Tan J, Siddireddy JS, Wong K, Shen Q, Vijay AK, Stapleton F. Factors Affecting Microbial Contamination on the Back Surface of Worn Soft Contact Lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 2021;98(5):512-7.

- The College of Optometrists. Myopia management: Control and care for children who are short-sighted 2024 [09 Oct 2025]. Available from: https://lookafteryoureyes.org/eye-care/myopia-management-control-eye-care-for-children-who-are-short-sighted/.

- Ophthalmology AAO. What is Orthokeratology? 2023 [09 Oct 2025]. Available from: https://www.aao.org/eye-health/glasses-contacts/what-is-orthokeratology.

- Gifford KL. Childhood and lifetime risk comparison of myopia control with contact lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020;43(1):26-32.

- Jung S, Eom Y, Song JS, Hyon JY, Jeon HS. Clinical features and visual outcome of infectious keratitis associated with orthokeratology lens in Korean pediatric patients. Korean J Ophthalmol 2024;38(5):399-412.

Latest Articles

HCP Popup

Are you a healthcare or eye care professional?

The information contained on this website is provided exclusively for healthcare and eye care professionals and is not intended for patients.

Click ‘Yes’ below to confirm that you are a healthcare professional and agree to the terms of use.

If you select ‘No’, you will be redirected to scopeeyecare.com

This will close in 0 seconds