Not your average pre-septal cellulitis

Patient presentation:

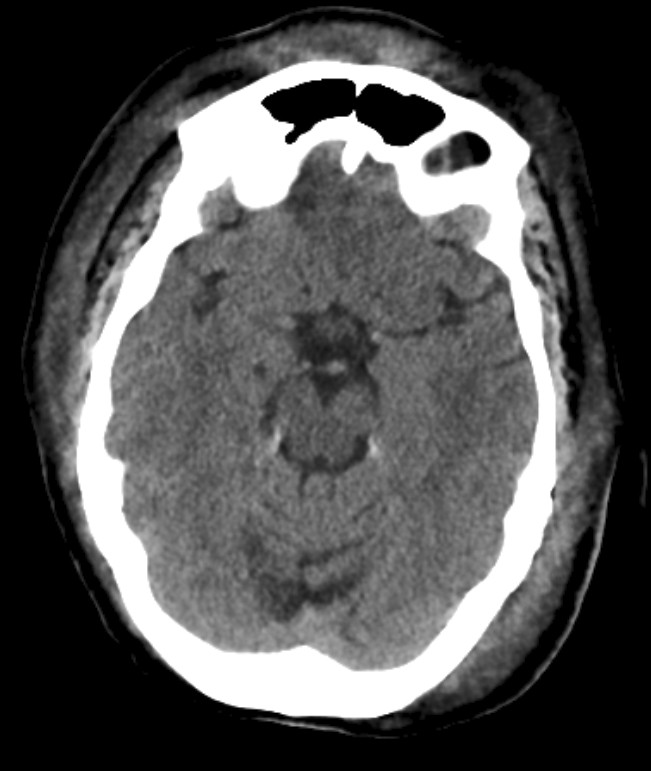

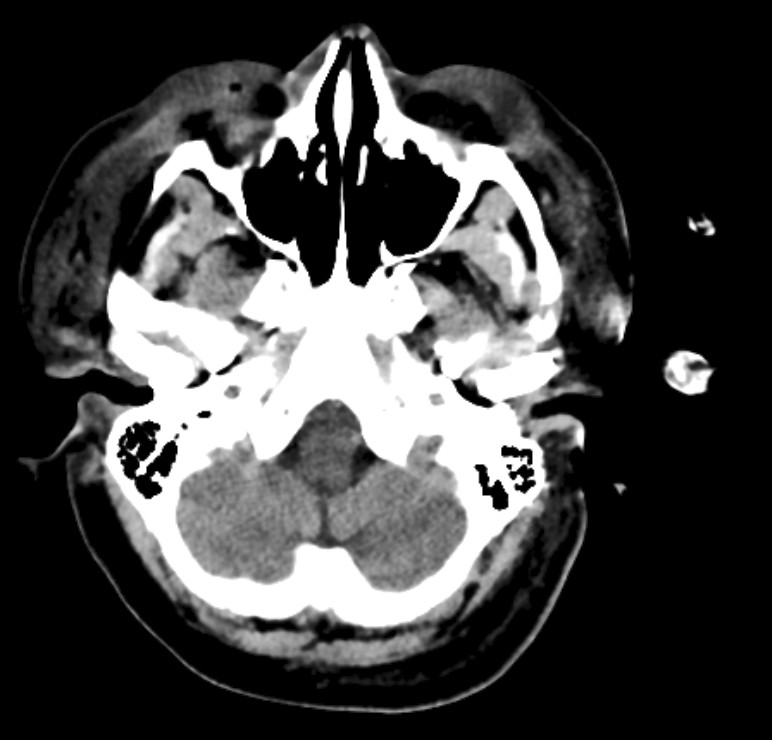

A 63-year-old female was admitted under the medical team for facial cellulitis with unknown cause. She was a known type-2 diabetic and also had hypertension. Her symptoms of periocular swelling, erythema and pain started following treatment for shingles from her GP. Once admitted, she began treatment of clindamycin, metronidazole, and ceftriaxone intravenously. Her admission CT scan (figure 1) demonstrated diffuse subcutaneous oedema extending over her face and eyelids, with no well-defined abscess. The swelling was confined to the pre-septal Tissue and there was no orbital involvement. There was also diffuse swelling of her Parotid glands bilaterally, but again no abscess was present. Eye swabs were taken on admission.

On day 5 of her admission, she was referred on to Ophthalmology and her admission swab results came back showing Group A Streptococcus Infection. I was the registrar on call, and on receiving the referral and reviewing the CT scan and swab results advised the medical team to speak to microbiology with regards to the antibiotics as my impression was that she had necrotising fasciitis. The antibiotics were changed to intravenous benzylpenicillin, clindamycin and oral metronidazole. The cefuroxime was stopped.

On reviewing the patient on the ward, I saw that she had blackened necrotic tissue on her right and left upper eyelids and left lower lid (figure 2) and she was listed for periocular debridement which took place the following morning. I carried out the periocular debridement and removed all necrotic tissue down to the septum or both upper lids and left lower lid. The wounds were left open to heal by secondary intention and topical chloramphenicol 1% was added to her antibiotic regime. Further discussion with microbiology led to the admission of vancomycin intravenously.

On post-operative day 2 (figure 3), her facial swelling had reduced on the left-hand side and both her eyes were opening spontaneously. Although there was some initial improvement (figure 4) with the periocular debridement, on day 16 her right lid swelling was noted to be increasing and it was thought that this was due to a central fluctuant forehead collection that was tracking down her nasal bridge and into her right upper lid. She was referred on to the maxillofacial team for urgent debridement of the forehead collection. They carried out drainage of her forehead and parotid collection on day 17. The maxillofacial team noted a necrotic galea layer with intact skin, involving occipitofrontalis and extending from the glabella across the left vertex of the skull, and across to the right temporal region. Benzylpenicillin was stopped following this operation.

The patient went on to have a further 2 operations under the maxillofacial team to remove necrotic tissue around the right buccal fat pad and the right temporal region. Following the second procedure a right facial nerve palsy was noted, likely to be iatrogenic (figure 5). The patient was placed on additional lubricants for this, xalin night. On day 19, microbiology advised a step down of antibiotics to intravenous co-amoxiclav, however she was later found to have vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Her antibiotics were changed again to meropenem and linezolid.

On day 42, she was discharged from hospital with oral linezolid and ciprofloxacin. She attended the outpatient Oculoplastic clinic one month after discharge and was found to have palpebral apertures of 10mm in the right eye and 8 in the leY, and lagophthalmos of 5mm in her right eye (figure 6). She was advised to take Thealoz Duo gel TDS to the right eye with carbomer gel at night and was started on maxitrol ointment BD to all four eyelids. We will continue to review her regularly and decide if any further lid surgery is required in due course.

Diagnostic testing:

Figure 1: Axial CT scan images from day 2 of admission.

Figure 5: Photos taken on day 30 of admission. (a) both eyes open (b) attempted eye closure showing right lagophthalmos.

Figure 6: Photos taken one month after discharge from hospital. (a) both eyes open (b) attempted eye closure showing right lagophthalmos.

Diagnosis and management

This patient had a delayed diagnosis of necrotising fasciitis. On reviewing the CT scans when the Patient was referred to Ophthalmology, I felt there were some suspicious signs of necrotising fasciitis, particularly the appearance of intraTssue air on the scans. This along with the eyelid swab results that grew Group A Streptococcus confirmed to me that the patient had necrotising fasciitis and would need urgent debridement of necrotic tissue to limit the spread. Once the diagnosis was made, she went on to have regular microbiology input and four operations – one under ophthalmology and three under the maxillofacial team.

Follow-up

Whilst an inpatient, she had regular Ophthalmology review on the ward and since discharge has been followed up in the oculoplastic clinic. The debridement carried out by the maxillofacial team has resulted in a right iatrogenic facial nerve palsy, though this is managed well at present with ocular lubricants.

Conclusions

This is a complex case of necrotising fasciitis. The learning points from this case include early recognition of the condition with early referral on to the Ophthalmology team. Our patient had a delayed diagnosis and delayed referral to the Ophthalmology team, possibly resulting in a more widespread infection.

A limited debridement of the upper and lower lids in the first instance is important to ensure the Patient has good long term function of the eyelids. In our Patient this initial limited operation ensured that there was no more skin affected and the disease was limited to the subcutaneous tissue only. This could be dealt with by laying the skin and debriding necrotic tissue underneath, as done by the maxillofacial team, and allowed for a better cosmetic outcome for the Patient.

Another learning point is to not rush in to a skin graft for the debrided areas on the eyelids. This is because, whilst the patient has active infection it is likely that the skin graft will not take very well due to a hostile environment. As we can see from our patient, often the skin heals well by secondary intention. We can always assess the need for a skin graft further down the line when the infection has settled.

Latest Articles

HCP Popup

Are you a healthcare or eye care professional?

The information contained on this website is provided exclusively for healthcare and eye care professionals and is not intended for patients.

Click ‘Yes’ below to confirm that you are a healthcare professional and agree to the terms of use.

If you select ‘No’, you will be redirected to scopeeyecare.com

This will close in 0 seconds