Management of Fungal Keratitis with Superficial White Plaques

Case 1

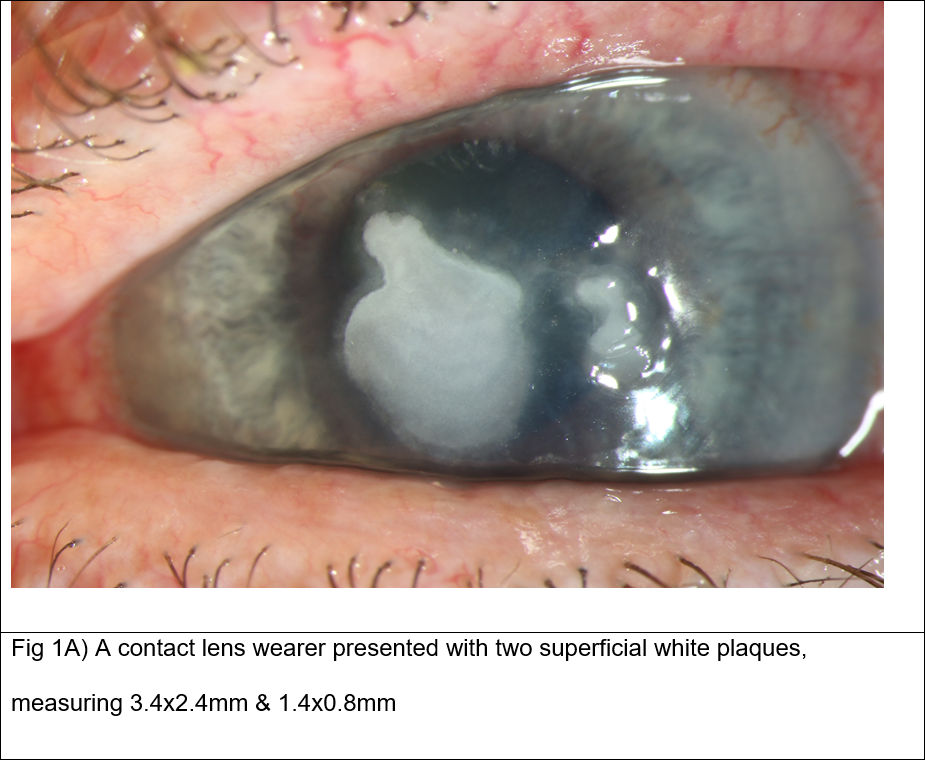

Patient presentation: A 61-year-old woman, who wore monthly contact lenses (CL), presented with sore left eye. She was started on hourly G.Levofloxacin at the first visit for presumed bacterial keratitis. Her corneal ulcer did not improve and 2 months later, she presented with two superficial white plaques, measuring 3.4×2.4mm and 1.4×0.8mm on slit-lamp (Fig 1A).

Diagnostic testing: Corneal scrape was performed, but did not yield any organism on microscopy or on culture. In-vivo confocal microscopy demonstrated multiple pseudo hyphae-like structures in stroma, with multiple round hyper-reflective yeast cells in the epithelium and stroma.

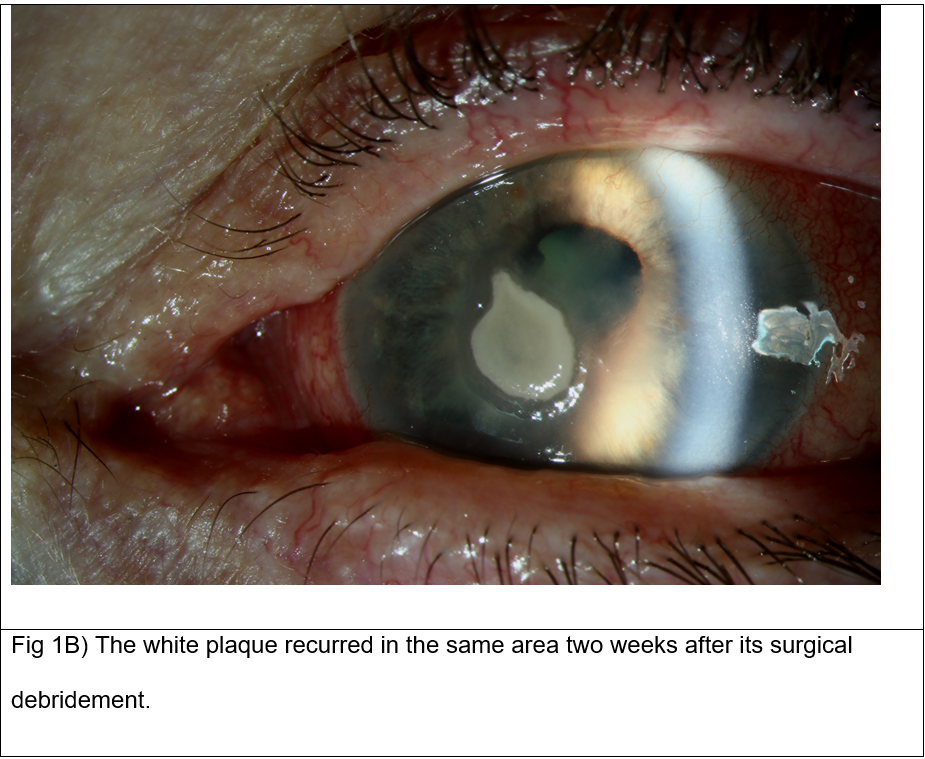

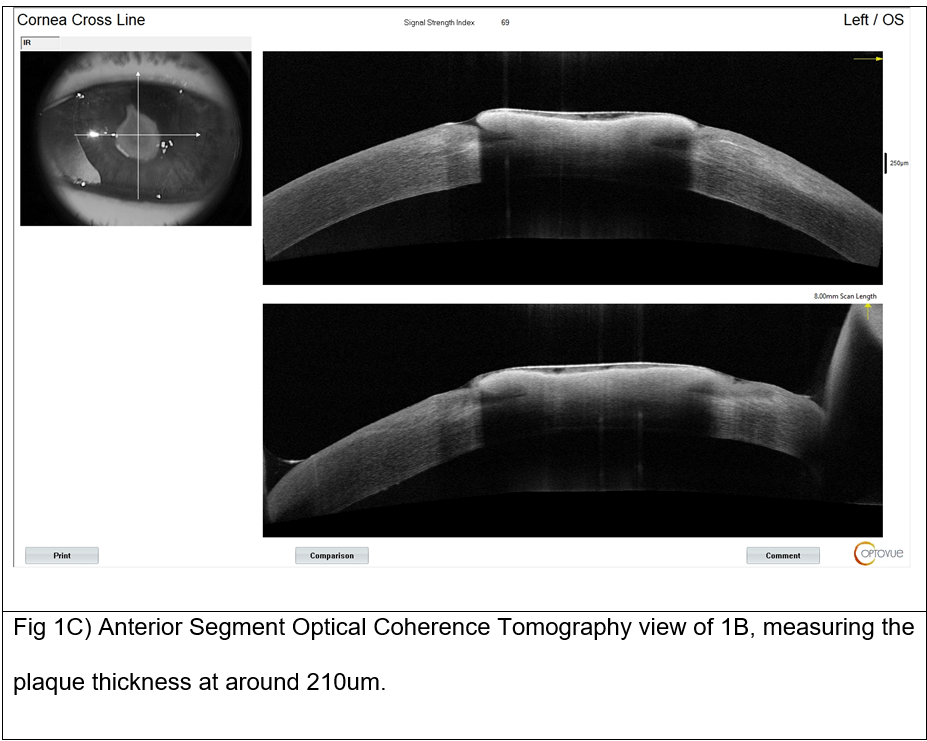

Diagnosis and Management: She underwent surgical debridement of the plaque, which was sent for microbiological analysis. Arthrographis kalrae was identified and noted to be sensitive to Voriconazole, Amphotericin B and Natamycin. A diagnosis of fungal keratitis was made and she was swiftly started on hourly G. Amphotericin B and G. Natamycin. Two weeks later, while she was still on the anti-fungal eyedrops, the white plaque recurred with a thickness of around 220um, as measured by AS-OCT (Fig 1B-C).

We performed intrastromal Voriconazole injection and another surgical plaque debridement. Histology report revealed that at multiple planes of the specimen, necrotic material could be seen with fungal hyphae running through its entirety.

Follow-up: Over the next six months, she was continued on G. Amphotericin B and slowly recovered with a paracentral corneal scar. Patient declined further surgical intervention and was discharged back to her local unit for visual rehabilitation with CL. She was able to achieve LogMAR 0.1 vision with CL.

Case 2

Patient presentation: A 59-year-old woman presented with dry, gritty eyes and was noted to have left corneal abrasion with loose epithelium, which was debrided in the eye emergency clinic. She was discharged with Chloramphenicol ointment and lubricant eyedrops. One month later, she returned with infective keratitis with anterior chamber activity and was commenced on intensive G. Cefuroxime and G. Levofloxacin treatment for assumed bacterial cause.

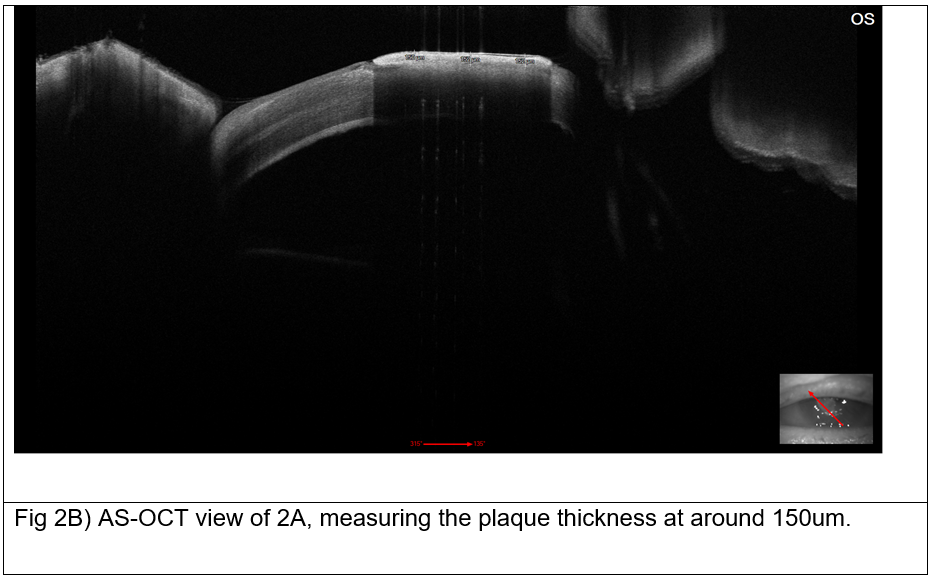

Diagnostic testing: Corneal scrape was performed and PCR sequencing identified Saccharomyces cerevisiae. G. Amphotericin B was added to the treatment regimen. Two weeks later, the patient developed a superficial white plaque measuring 2.8×2.8mm, with a thickness of around 150um as measured by AS-OCT (Fig 2A-B).

Diagnosis and Management: She underwent surgical plaque debridement and intrastromal Voriconazole injection. Interestingly, histological study of the plaque specimen revealed no convincing fungal spores or hyphae, and no fungus could be identified even after two weeks of incubation. Patient was continued on G. Amphotericin B.

Follow-up: Her cornea healed with a paracentral scar over the next 2 months. Her final best-correct visual acuity (BCVA) was LogMAR 0.4.

Conclusions

Fungal keratitis remains a significant cause of corneal blindness worldwide. Its global incidence has been estimated at between 1 and 1.4 million cases, with about 100,000 eyes being surgically removed annually as a result.(1) Majority of fungal keratitis are caused by filamentous fungi Fusarium and Aspergillus spp and yeast Candida spp. Fungal keratitis appears to disproportionately affect lower-income countries with hot, humid climate; an association has been demonstrated between regions with higher proportion of infective keratitis cases that were fungal in nature, and lower gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.(1)

Fungal corneal plaques can form superficially and on the endothelial surface. Cases of retro-corneal fungal plaques have previous been published,(2, 3) with largely favourable clinical outcomes reported after their surgical aspiration or debulking intraocularly. Corneal surface plaques secondary to fungal and other infective agents have infrequently been reported in the past, all in the Asian countries.(4, 5, 7-10) Both white and pigmented surface plaques have previously been described, with the latter caused by dematiaceous fungal species.(4-6) While the majority of these were of fungal origin (22 out of 25; 88%), they are not the only infectious causative agents for surface plaque formation; surface plaques have been attributed to bacterium and acanthamoeba as well.(7, 8)

AS-OCT can provide cross-section images of the cornea in high resolution that can be used to objectively assess microbial keratitis, such as the depth of infiltrate involvement and its response to treatment over time.(11) To our knowledge, this is the first time AS-OCT has been used to measure and document superficial fungal plaques.

Previous studies (4, 7) have suggested that colonies of fungi and bacteria found within the debrided superficial plaque structures may be a form of pathogen entrapment, which explains why such infections rarely advance deeper into the stromal layers, and why these patients only develop mild to moderate inflammation and clinical features.

Our experience chimed with previously published works that physical excision of the surface plaque may be important in the resolution of fungal or other infections, by reducing pathogen load on the infective ulcer.(4, 8) In addition, physical removal of surface plaques may also serve to improve topical drug delivery directly onto the ulcer bed.

Deep-seated keratomycosis can be unresponsive to topical anti-fungal treatment. Previous studies proposed intrastromal voriconazole injections as an effective treatment modality for recalcitrant fungal keratitis not responding to topical anti-fungals, with largely favourable outcomes at between 72 and 83% success rates.(13, 14) Sharma et al concluded that intrastromal drug delivery may be more efficacious than topical or systemic routes, as it can deliver high drug concentration at the infection site. We also administered intrastromal voriconazole in our two cases.

In conclusion, fungal keratitis can be challenging to diagnose, and subsequent delay in initiating optimal treatment can lead to poor clinical outcome. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of fungal keratitis in patients presenting with corneal plaques. Fungal species may not be detected on direct microscopy of corneal smears; other diagnostic modalities including in-vivo confocal microscopy, culture and PCR may be required for accurate diagnosis. Treatment with topical and intrastromal anti-fungal agents and/or surgical debridement may be necessary for successful resolution. Close follow-up and monitoring are essential to detect and manage recurrent or persistent plaques.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ophthalmic photography team at Bristol Eye Hospital for their contributions.

References

- Brown L, Leck AK, Gichangi M, Burton MJ, Denning DW. The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(3):e49-e57.

- Kitazawa K, Fukuoka H, Inatomi T, Aziza Y, Kinoshita S, Sotozono C. Safety of retrocorneal plaque aspiration for managing fungal keratitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2020;64(2):228-33.

- Palioura S, Tsiampali C, Dubovy SR, Yoo SH. Endothelial Biopsy for the Diagnosis and Management of Culture-Negative Retrocorneal Fungal Keratitis With the Assistance of Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging. Cornea. 2021;40(9):1193-6.

- Garg P, Vemuganti GK, Chatarjee S, Gopinathan U, Rao GN. Pigmented plaque presentation of dematiaceous fungal keratitis: a clinicopathologic correlation. Cornea. 2004;23(6):571-6.

- Chaidaroon W, Supalaset S, Tananuvat N, Vanittanakom N. Corneal Phaeohyphomycosis Caused by. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2016;7(2):364-71.

- Tsai TH, Chen WL, Peng Y, et al. Dematiaceous fungal keratitis presented as a foreign body-like isolated pigmented corneal plaque: a case report. Eye (London, England). 2006;20(6).

- Cho BJ, Lee YB. Infectious keratitis manifesting as a white plaque on the cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(8):1091-3.

- Sahu SK, Das S, Sharma S, Vemuganti GK. Acanthamoeba keratitis presenting as a plaque. Cornea. 2008;27(9):1066-7.

- Tsai T, Chen W, Peng Y, Wang I, Hu F. Dematiaceous fungal keratitis presented as a foreign body-like isolated pigmented corneal plaque: a case report. Eye (London, England). 2006;20(6).

- Todokoro D, Eguchi H, Yamada N, Sodeyama H, Hosoya R, Kishi S. Contact Lens-Related Infectious Keratitis with White Plaque Formation Caused by Corynebacterium propinquum. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(9):3092-5.

- Konstantopoulos A, Kuo J, Anderson D, Hossain P. Assessment of the use of anterior segment optical coherence tomography in microbial keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(4):534-42.

- Garg P, Gopinathan U, Choudhary K, Rao GN. Keratomycosis: clinical and microbiologic experience with dematiaceous fungi. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(3).

- Kalaiselvi G, Narayana S, Krishnan T, Sengupta S. Intrastromal voriconazole for deep recalcitrant fungal keratitis: a case series. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2015;99(2).

- Sharma N, Agarwal P, Sinha R, Titiyal JS, Velpandian T, Vajpayee RB. Evaluation of intrastromal voriconazole injection in recalcitrant deep fungal keratitis: case series. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2011;95(12).

Latest Articles

HCP Popup

Are you a healthcare or eye care professional?

The information contained on this website is provided exclusively for healthcare and eye care professionals and is not intended for patients.

Click ‘Yes’ below to confirm that you are a healthcare professional and agree to the terms of use.

If you select ‘No’, you will be redirected to scopeeyecare.com

This will close in 0 seconds