A Tearful Affair: a Case of Lacrimal Sac Lymphoma

Patient Presentation

A 77 year old female patient was under the vitreo-retinal clinic for four years, for monitoring of left macular retinoschisis secondary to vitreous peripapillary traction. She had a past medical history of asthma, hypertension and bowel cancer (15 years ago, treated in Australia with resection and chemo-radiotherapy) and a past ocular history of right mild amblyopia secondary to strabismus and bilateral pseudophakia. She was independent with minimal alcohol intake, did not smoke and enjoyed playing music.

At routine vitreo-retinal follow-up, she disclosed ongoing left epiphora, worse outdoors, with an 8 month history of a left medial canthal erythematous lump. There was no history of trauma, previous surgery, haemolacria or epistaxis. She was referred routinely to the oculoplastic service with a suspicion of chronic dacryocystitis.

3 months later, whilst awaiting her routine appointment, she presented to her optometrist with the lump getting progressively larger with worsening redness. She denied pain or visual disturbance. Suspecting acute dacryocystitis, she was referred to the hospital eye casualty.

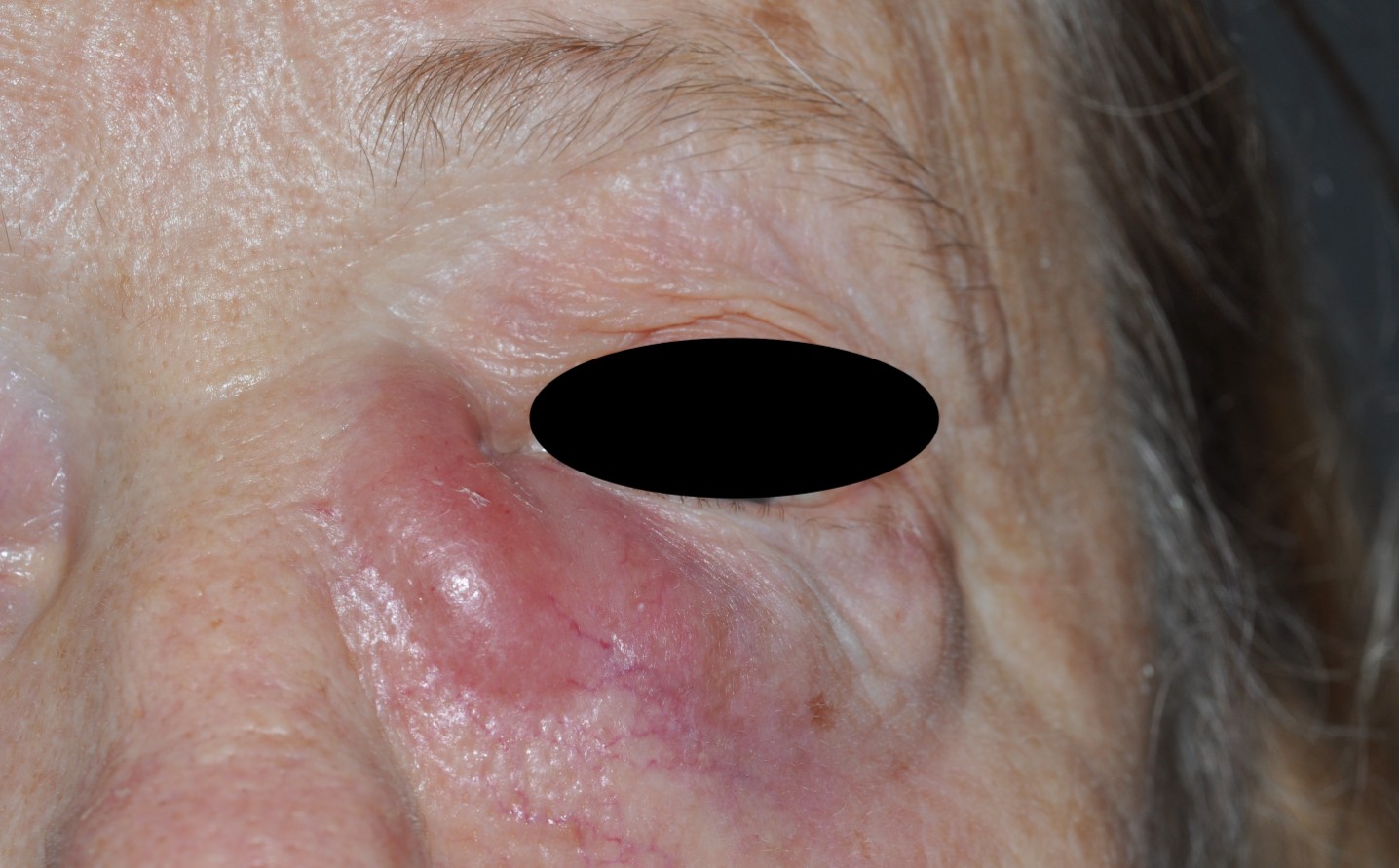

Examination in eye casualty revealed a best corrected visual acuity of 6/9 (right eye) and 6/6 (left eye). Intraocular pressures were 15 mmHg (right eye) and 13 mmHg (left eye). Adnexal examination showed an erythematous raised lump overlying the left lacrimal sac (figure 1). Her slit lamp examination was otherwise in status quo, with a white eye, quiescent pseudophakia and stable posterior segment.

A diagnosis of acute-on-chronic dacryocystitis was made. The patient was commenced on co-amoxiclav 625 mg and metronidazole 400 mg, each three times a day for 1 week.

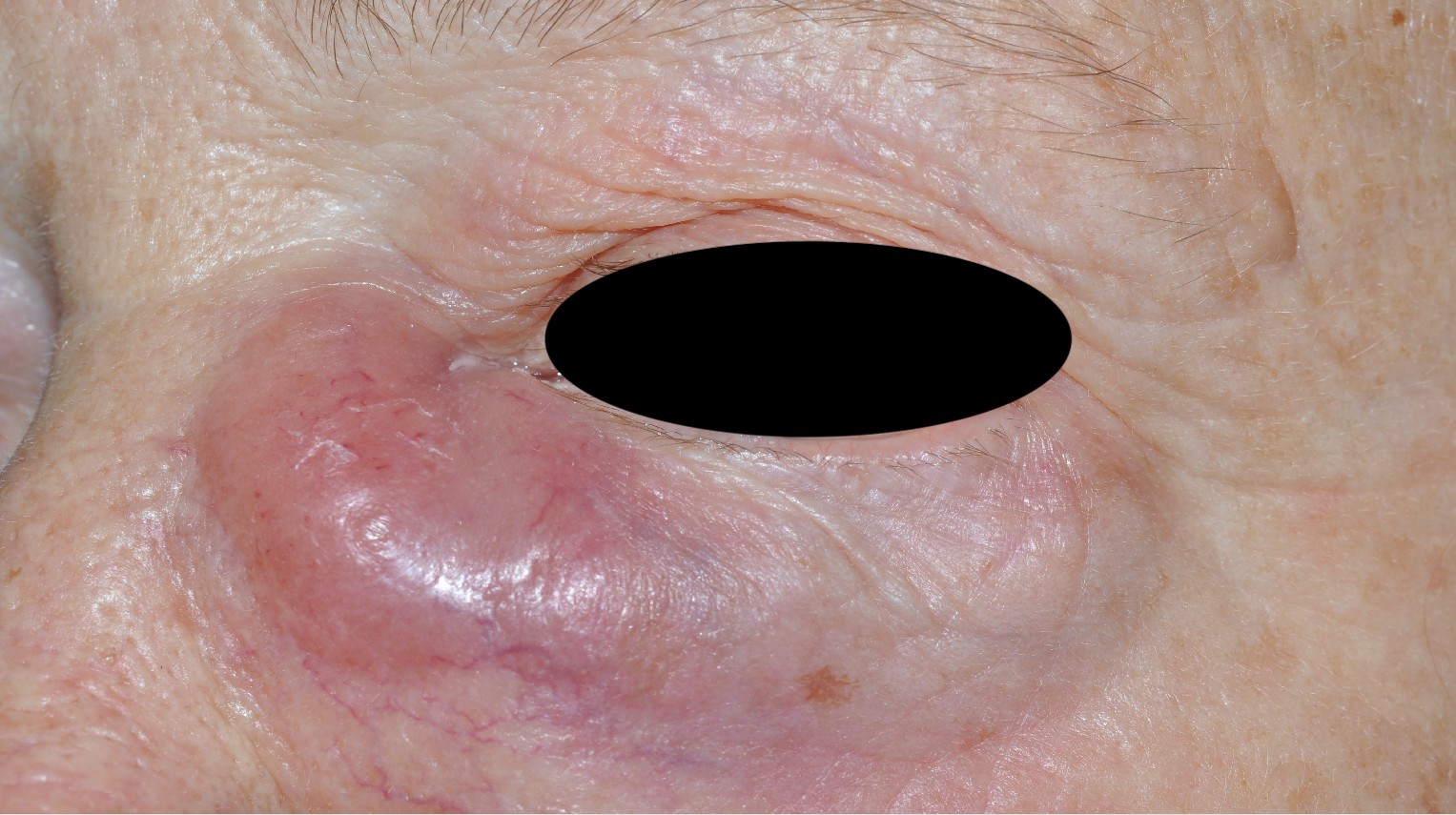

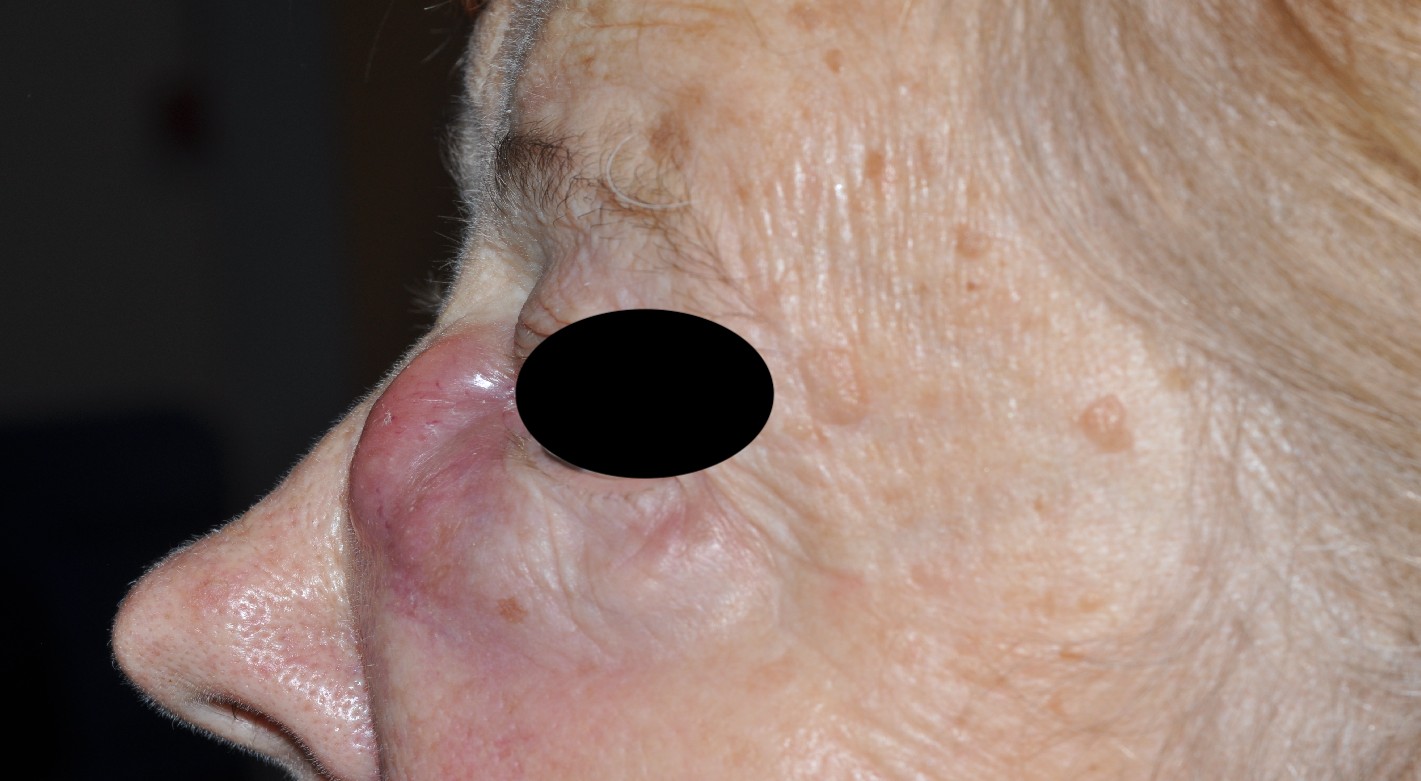

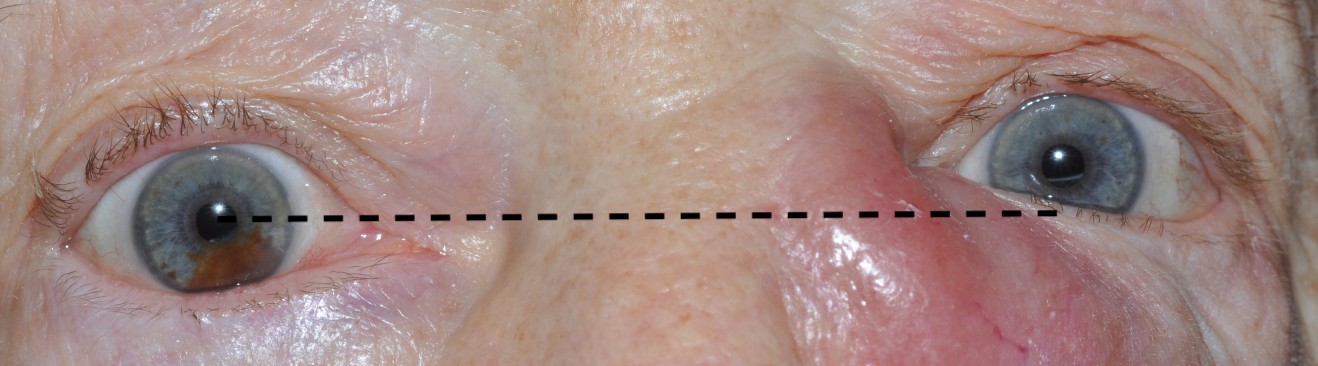

At 1-week follow up in the oculoplastic service, there was no significant improvement on oral antibiotics. Visual acuity was stable and extraocular movements were full. Examination of the left periorbit revealed a 4 x 5 cm firm, tense, tender, irregular, erythematous swelling, extending from the left side of her nose to the upper cheek with induration palpable even below the erythematous area (figures 2-3). Palpation did not produce mucus regurgitation from the puncta. Her puncta were well-opposed to the globe and of a good size. Her conjunctivae were white and quiet with clear corneas. Fluorescein dye disappearance test and tear film meniscus height was normal and symmetrical between the eyes. Lacrimal syringing was attempted with difficulty due to lack of space secondary to the lesion, however was found to be at least partially patent, with minimal non-mucoid regurgitation from the superior canaliculus.

An urgent computed tomography (CT) scan was requested to rule out malignancy; she was simultaneously placed on the waiting list for an urgent external dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) for what was thought to be a probable mucocele secondary to primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

Diagnostic Testing

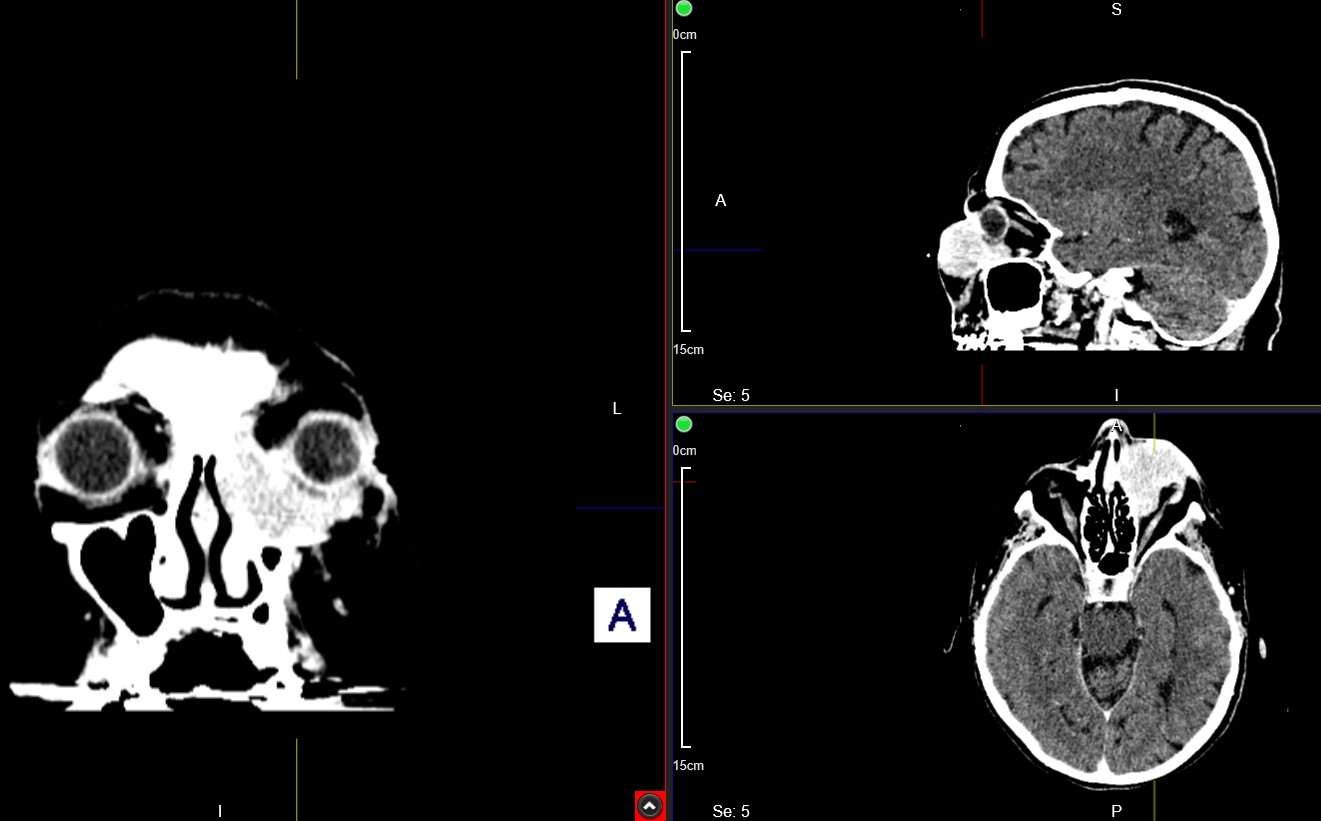

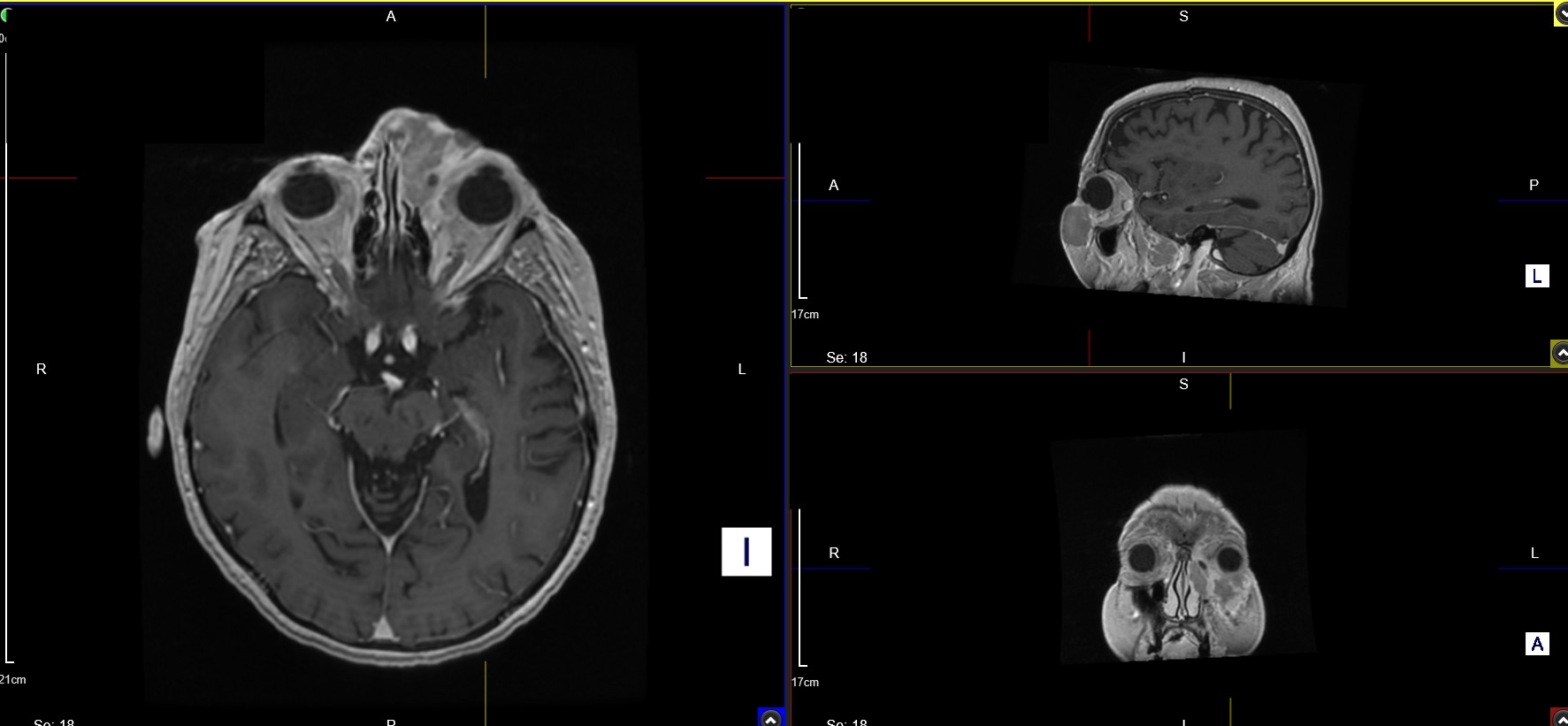

CT orbits with contrast revealed a 2.7 x 3 cm lobulated left-sided mass, appearing to originate from the nasolacrimal sac, with the bulk of the lesion extending extra-conally into the left medial orbit along the inferior orbital rim, abutting the medial aspect of the inferior rectus muscle (figures 4-5). There was medial extension into the anterior ethmoid air cells and anterior third of the superior nasal passage, with bony erosion and irregularity of the left nasal bone, the lamina papyracea as well as suggestion of erosion of the inferior orbital bone. Anteriorly, the lesion extended very close to the subcutaneous tissues of the inferior orbital rim with likely impending breach of the skin – overall an appearance highly concerning for a neoplastic malignant progress.

The patient was informed of the result and recalled urgently to clinic for a full orbital assessment. Examination revealed stable visual acuity with 1 mm of proptosis and 1.5 mm of hyperglobus (figure 6). There was no chemosis. Orbital retropulsion was soft. Ishihara colour plates were full and fast in both eyes with no red desaturation. Pupil reactions were normal with no relative afferent pupillary defect.

An urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the sinuses with contrast was requested, which showed a lobulated 36 x 29 mm T1 hypointense and mildly enhancing mass extending into the soft tissues of the cheek, into the nares and down along the line of the nasolacrimal sac, with extraconal extension into the left orbit where the lesion was closely applied to the left medial rectus muscle, consistent with a neoplasm (figure 7). An MRI head with contrast showed no signs of an expanding intracranial mass.

The DCR was placed on hold until her case was discussed at the head and neck / ear, nose and throat multidisciplinary team (MDT).

An urgent nasal surgeon assessment revealed a normal naso-endoscopy with no tumour seen in the nose, but compromised left nasal airway from mass effect. Her oral cavity and oropharynx were normal. Nasal punch biopsies were taken. Histopathology showed a diffuse monotonous population of large atypical lymphocytes, suggestive of a high-grade lymphoproliferative disorder. An expert second opinion from London confirmed diffuse infiltration by atypical medium to large lymphoid cells, extending from the upper dermis to the subcutis showing immunoblastic and centroblastic morphology with scattered apoptotic bodies and mitotic figures (Ki-67 >90% [Ki-67 is a nuclear protein involved in cell regulation; expression is widely used as a proliferation marker in cancers including lymphoma], positive for CD20, CD5, BCL20, BCL6,). Immunophenotyping was consistent with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. She denied any B symptoms (fever, night sweats or weight loss).

Further Investigations, Diagnosis and Management

A subsequent staging CT neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis was performed; confirming the paranasal lesion with erosion into the ipsilateral nasal bone, nasal processes and frontal maxillary bone with close contact to the medial and inferior rectus muscles and a smaller satellite nodule in the soft tissues of the left anterior cheek. Small volume ipsilateral submandibular, jugulodigastric and lateral cervical adenopathy was noted. No sinister lung lesions were noted. A hepatic dome subcapsular hypodense lesion of 4.4 x 2.8 cm was noted, with no obvious large bowel mass.

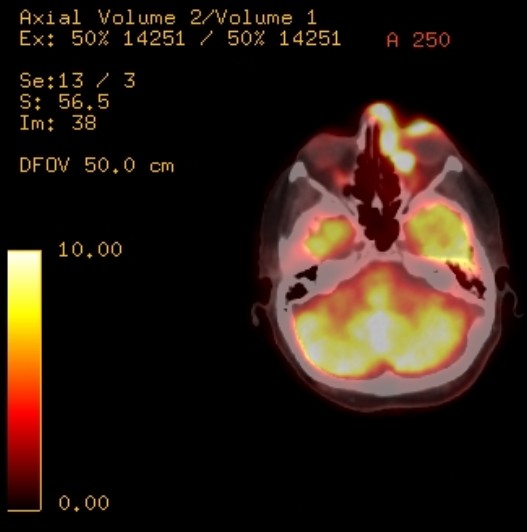

She was thereby referred to the haematology team for assessment; full blood count, renal function and bone profiles were within normal limits. She was sent to nuclear medicine for Positron Emission Tomography Computed Tomography (PET-CT), which confirmed the CT findings with no other areas of nodal involvement (figure 8).

The patient was counselled on her diagnosis of lacrimal sac lymphoma, and offered R-Mini-CHOP chemo-immunotherapy (rituximab-cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisone). ‘Mini’ indicates an attenuated version, for our elderly patient who was unlikely to tolerate the full-dose, aiming for 6 cycles as tolerated.

Follow Up and Clinical Outcome

The patient agreed to proceed with R-Mini-CHOP chemotherapy under the haematology team. She tolerated her first cycle well with a significant improvement to the appearance of the prominent facial mass (figure 9).

She is currently undergoing her subsequent cycles and remains under close follow-up with haemato-oncology and ophthalmology.

Conclusions and Learning Points

This 77 year old patient’s case highlights an important lesson: lacrimal sac lymphoma – though rare – can be fatal – and must be excluded in atypical ‘dacryocystitis’ cases. Parts of her presentation, in retrospect, were not typical for dacryocystitis (no pain – although chronic dacryocystitis can also be painless, and no mucous regurgitation from lacrimal sac palpation). However, she also did not have typical naso-lacrimal obstructive signs (normal fluorescein dye disappearance test and tear film meniscus height). Early diagnosis was crucial to prevent further infiltration, and was suspected at the time of no response to systemic antibiotics. With appropriate and timely investigation and multidisciplinary team involvement, her tumour continues to respond well to treatment.

Lymphomas, or cancers of the lymphatic system are grouped broadly into Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). NHL are further classified as low-grade (indolent) or high-grade (aggressive).

Orbital, or ‘ocular adnexal lymphoma’ (OAL) refers to lymphoma in the orbit, eyelids, conjunctiva, lacrimal gland and lacrimal sac – as opposed to intra-ocular lymphoma.1 Hodgkin lymphoma rarely causes ocular disease; hence OAL is almost exclusively NHL. The most common subtype is B-cell lymphoma (either mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, extranodal marginal B-cell lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL] – especially in lacrimal sac lymphoma, as in our case). Overall, OAL is rare, representing only 1% of all NHL.2

Lymphomas of the lacrimal sac are furthermore extremely rare, especially when primarily originating from the lacrimal sac rather than being secondary to systemic lymphoma metastases.3 These are found in older patients (median age 71 years).4 Clinical presentation includes painless medial canthal swelling and epiphora; lacrimal sac lymphoma can therefore often be misdiagnosed, as in this case, as dacryocystitis secondary to primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction.4,5 The initial diagnosis is often incorrect and lymphoma may only be diagnosed late – following biopsies of the lacrimal sac taken when ‘dacryocystitis’ recurs following dacryocystorhinostomy, for instance. Diplopia is less frequent as a symptom, and can be caused by invasion of intraocular muscles. Clinical examination may reveal a palpable lesion above the level of the medial canthal tendon – a red flag for a lacrimal sac malignant neoplasm. Other differentials for a medial canthal / lacrimal sac mass include mucocele, granulomatous inflammation (e.g. sarcoidosis or idiopathic), dermoid cyst, lipoma, lymphangioma and other tumours such as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma.5

CT (to view bony detail) and MRI (for soft tissue detail) scans with contrast can help guide diagnosis and aid staging. Diagnosis can be further confirmed by histopathology with immunophenotyping and flow cytometry on tissue biopsy, which in our patient’s case was performed endonasally.7 Bone marrow examination and PET scanning can be undertaken to aid staging and monitor for treatment response. Blood tests can aid determination of systemic sequelae and are required as a baseline for chemo/immunotherapy. Grading and staging is via the Ann Arbor system, accounting for growth rate and confinement to orbit / adjacent structure involvement / nodal disease.8

Moving away from therapeutic surgery due to the risk of injury to vital ocular structures and relapse risk, chemotherapy is now considered the standard management option for localised high-grade NHL or disease with adjacent structure / nodal involvement, with either CHOP therapy alone or with adjuvant radiotherapy.9 Our patient had the addition of rituximab (R-CHOP), an anti-CD20 immunotherapy agent, due to her DLBCL expressing CD20 antigen on the cell surface. This has a significant benefit compared to using chemotherapy alone with regard to response rate, progression-free survival and overall survival.10

Where chemotherapy cannot be tolerated due to advanced comorbidities or poor performance status, or where tumours are indolent and localised, radiotherapy may be offered to prevent local and systemic sequelae and preservation of visual acuity.5

Poor prognostic factors include older age, elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, higher stage and grade and presence of B symptoms.11 Life-long follow up is required to monitor for complications, recurrence and metastases.7

In conclusion, lacrimal sac lymphoma – albeit rare – is essential to diagnose early to avoid sinister local or systemic sequelae.11 Recent literature also reveals patients of certain ethnicities and with certain facial anatomical features presenting with naso-lacrimal duct obstruction are more likely to have secondary causes.13-14 Learning points from this patient’s case include:

- Be suspicious of lacrimal sac masses that extend superior to the medial canthal

- Perform naso-lacrimal syringing in clinic for unilateral, constant

- Consider secondary or sinister causes and investigate promptly especially if features are inconsistent with dacryocystitis e.g. no epiphora, no pain or no response to

A broad differential diagnosis, swift multidisciplinary team involvement, and open patient-communication were essential in resulting in a positive outcome for this patient.

References

- Yadav BS, Sharma Orbital lymphoma: role of radiation. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57(2):91-97. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.44516

- Fitzpatrick PJ, Macko S. Lymphoreticular tumors of the orbit. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984;10(3):333-340. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(84)90051-8

- Sjö LD, Ralfkiaer E, Juhl BR, et Primary lymphoma of the lacrimal sac: an EORTC ophthalmic oncology task force study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(8):1004-1009. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.090589

- Ueathaweephol S, Wongwattana P, Chanlalit W, Trongwongsa T, Sutthinont Lacrimal sac lymphoma: a case report. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2022;23(1):43-47. doi:10.7181/acfs.2022.00612

- Montalban A, Liétin B, Louvrier C, et Malignant lacrimal sac tumors. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2010;127(5):165-172. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2010.09.001

- Venkitaraman R, George Primary non Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the lacrimal sac. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:127. Published 2007 Nov 6. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-5-127

- Parmar DN, Rose GE. Management of lacrimal sac tumours. Eye (Lond). 2003;17(5):599-606. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700516

- Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. Springer,

- Venkitaraman, , George, M.K. Primary non Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the lacrimal sac. World J Surg Onc 5, 127 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-5-127

- Decaudin D, de Cremoux P, Vincent-Salomon A, Dendale R, Rouic LL. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a review of clinicopathologic features and treatment options. Blood. 2006;108(5):1451-1460. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-02-005017

- Tsao WS, Huang TL, Hsu YH, Chen N, Tsai Primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the lacrimal sac. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2016;6(1):42-44. doi:10.1016/j.tjo.2014.11.002

- Neerukonda VK, Stagner AM, Wolkow N. Lymphoma of the Lacrimal Sac: The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Experience With a Comparison to the Previously Reported Literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;38(1):79-86. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001997

- Lin Z, Kamath N, Malik High-resolution computed tomography assessment of bony nasolacrimal parameters: variations due to age, sex, and facial features. Orbit. 2021;40(5):364-369. doi:10.1080/01676830.2020.1793374

- Lin Z, Kamath N, Malik A. Morphometric differences in normal bony nasolacrimal anatomy: comparison between four ethnic groups. Surg Radiol Anat. 2021;43(2):179-185. doi:10.1007/s00276-020-02614-4

Latest Articles

HCP Popup

Are you a healthcare or eye care professional?

The information contained on this website is provided exclusively for healthcare and eye care professionals and is not intended for patients.

Click ‘Yes’ below to confirm that you are a healthcare professional and agree to the terms of use.

If you select ‘No’, you will be redirected to scopeeyecare.com

This will close in 0 seconds