Glaucoma in People of Black Ethnic Background

Glaucoma is an indiscriminate disease that can affect people of any age, ethnic background or health status. However, there are well known genetic, environmental and clinical risk factors that can significantly increase the prevalence of the different types of glaucoma. One of the risk factors for developing glaucoma that is particularly relevant is a person’s ethnic background, with black ethnic background being a considerable risk factor for the incidence of challenging to manage primary open angle glaucoma.

The 2021 Census of England and Wales asked people to self-identify into 5 main ethnic groups. The Black, Black British, Caribbean or African ethnic group accounted for approximately 4% (2.4milliion) of the population of England and Wales, an increase of approximately 0.5 million people compared to 2011. The distribution of the 2.4million people of black ethnic background however is very uneven. There is a concentration in urban areas, in particular London, Birmingham and Manchester, where people of black ethnic background can account for over 25% of the population.

There are noteworthy differences with glaucoma in people of black ethnic background that are important to be aware of which are summarised in Table 1. These differences are as a result of genetic variations but are likely to be compounded by environmental factors that can lead to less favourable outcomes.

The same 2021 Census of England and Wales also looked at household wealth and found that the ethnic group with the lowest household wealth was people of Black African ethnic background. The Annual Population Survey from the Office for National Statistics also identified pay gaps between all black ethnic groups compared to average, even when adjusted for the type of employment and demographic make-up. Education achievements were also found to be lowest in the black ethnic background group across GSCE, A level and university undergraduate level.

All together, these differences result in a group of people with a genetic predisposition to prevalent and aggressive glaucoma, but who also have socioeconomic factors that are likely to lead to late presentation.

Prevalence | ~5 times more prevalent compared to people of white ethnic background |

Age at presentation | Develops ~10 years earlier than in other ethnic groups, but people are only ~5 years younger at presentation |

Disease state at presentation | More advanced visual field loss at presentation compared to people of white ethnic background (-9.3dB vs -5.5dB) |

Rate of disease progression | Visual field loss progresses ~0.5dB/year more than in people of white ethnic background |

Frequency of blindness | Glaucoma related blindness is ~6 times more frequent compared to people of white ethnic background |

Frequency of visual impairment | Glaucoma related visual impairment is ~15 times more frequent compared to people of white ethnic background |

Table 1. Differences with glaucoma in people of black ethnic background

Diagnostic challenges

The African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study (ADAGES) was a prospective, multicentre observational cohort study of over 1000 participants of African descent and European descent with glaucoma, suspected glaucoma, or no evidence of glaucoma.

It identified some crucial physiological differences relevant to detecting glaucoma in people of Black ethnic background compared to White ethnic background as well as differences in clinical features at presentation.1

These are summarised in Table 2.

Physiological differences | Physiological differences Clinical features at presentation |

Optic nerve: – Larger size – Deeper cups – Greater cup:disc ratio | Visual field: – Worse central and peripheral damage – More variable results – More likely to be fast progressors |

Central corneal thickness ~10 microns thinner Intraocular pressure ~2.5mmHg higher | Intraocular pressure ~2.5mmHg higher |

Poor visual acuity twice as likely |

Table 2 Physiological and clinical features at presentation that significantly differ between people of Black ethnic background in comparison to people of White ethnic background

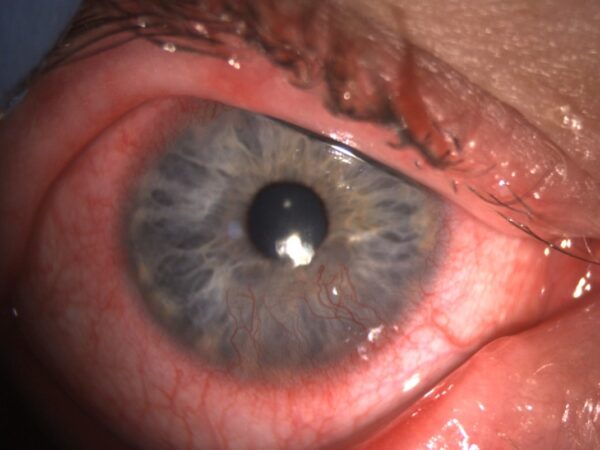

The physiological differences in the optic nerve are particularly important to understand when evaluating OCT scans for glaucoma. The automated analysis reports from commercial OCTs devices are based on a normative database that comprise of between just 12-22% of people of Black ethnic background. This leads to a greater rate of false positives and false negatives when interpreting scans of people of Black ethnic background. People of Black ethnic background were also found to be more susceptible to intraocular pressure (IOP) damage – in fact over 5 times more likely to develop visual field damage at a similar IOP. Despite this, there is less frequency of visual field testing in people of Black ethnic background.

Whilst stereotyping has its obvious dangers, the typical phenotype of glaucoma in people of Black ethnic background is of younger people with higher intraocular pressure and more advanced disease on presentation. Compared to people of White ethnic background it is more unusual (whist certainly still possible) for people of Black ethnic background to present with angle closure, normal tension glaucoma or glaucoma secondary to pseudoexfoliation or pigment dispersion syndrome.

Screening

Eye health screening represents another challenge for the detection of glaucoma in people of Black ethnic background. The socioeconomic differences previously mentioned, surmount to likely very real barriers to accessing care. Whilst free optometric eye testing is available for people with positive family history of glaucoma (another significant risk factor for developing glaucoma) from the age of 40, only in Wales does this also apply to ethnic groups at high risk of developing glaucoma. Unfortunately, this is only likely to have a limited impact as there are almost 10 times more people of black ethnic background just in the London boroughs of Southwark, Lambeth and Lewisham compared to the whole of Wales and unfortunately, in England, there currently is still a fee for testing high risk ethnic groups under the age of 60.

Management challenges

Underrepresentation in studies

Whilst the management of glaucoma has benefited from the evidence provided by a number of high quality randomised controlled trials in recent years, it is important to recognise that people of Black ethnic background are poorly represented in the majority of these landmark glaucoma studies. The United Kingdom Glaucoma Treatment Study (UKGTS) clearly demonstrated the benefit of treatment of open-angle glaucoma with latanoprost compared to a placebo eye drop.2 However, the trial only included less than 6% of patients of Black ethnic background. We know from the treatment of other health conditions like hypertension, that the response to different medication classes can significantly vary between different ethnic groups. It is therefore not inconceivable that there could be a clinically relevant difference in treatment response from the various available medications in people of Black ethnic background.

The Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension Trial (LiGHT) clearly demonstrated the benefits of selective laser trabeculoplasty compared to eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma,3but people of Black ethnic background only represented 20% of the trial’s participants. There is a similar story in the recent trials evaluating the efficacy of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery where people of Black ethnic background usually comprise less than 20% of the cohort of patients.4 Similar to the efficacy of intraocular pressure lowering medication, it is not inconceivable that there may be a difference in the efficacy of intraocular pressure lowering interventions between different ethnic groups.

Risk of failure of surgery

One of the very plausible reasons why interventions to lower intraocular pressure could be less successful in patients of Black ethnic background could be due to the well-known increased risk of scarring and inflammation in people of Black ethnic background. Trabeculectomy remains the gold standard operation for medically uncontrolled or advanced glaucoma and scarring of the drainage bleb needs to be prevented in order for it to be successful in lowering the intraocular pressure.

It has been repeatedly demonstrated that people of Black ethnic background have poorer outcomes of trabeculectomy surgery5and also aqueous humour drainage devices (tubes)6 which similarly rely on prevention of scarring of a bleb. Higher failure rates and greater risks of complications in patients of Black ethnic background raises the need for modifications to current surgical techniques or different treatment options altogether in order to improve outcomes.

Treatment barriers

Outpatient clinic non-attendance rates have been shown to be almost twice as high in patients of Black ethnic background and in fact, being of Black ethnic background was found to be a significant independent risk factor for inconsistent follow-up. Patients of Black ethnic background have also been found to have lower treatment adherence rates than patients of White ethnic background.

The inability to speak English obviously represents a language barrier to effective communication between a clinician and patient and some of the highest proportions of people who can’t speak English are found in people of Black ethnic background, particularly affecting females aged 65 year and over. The use of online translation software and online patient education resources with automated translation into a patients native language can significantly improve patient understanding and engagement in the management of their glaucoma.

Summary

Glaucoma in people of Black ethnic background represents a significant clinical and social challenge. The combination of a population with genetically driven risk factors for a higher prevalence of glaucoma as well as more aggressive disease, in combination with socioeconomic risk factors that result in barriers to accessing healthcare bring about a difficult starting point. This is further exacerbated by diagnostic challenges that can lead to late presentation for treatment, with more advanced disease. Given that it is significantly more challenging to treat advanced glaucoma, plus the poorer outcomes of glaucoma surgery in people of Black ethnic background, it is unsurprising that there are less favourable outcomes in this group of people. Overall, glaucoma in people of Black ethnic background has a significantly greater burden of disease which will only increase in future years. Therefore, further research focused on currently underrepresented ethnic groups as well as policy changes that can encourage earlier detection and treatment are much needed.

Take home messages

- Be aware that Glaucoma in people of Black ethnic background is significantly more prevalent, aggressive and likely to lead to visual impairment, therefore avoiding late presentation is crucial

- Recognise the physiological differences and limitations of OCT scans in people of Black ethnic background that can make detection of glaucoma challenging

- Appreciate that close observation is required throughout treatment given the greater risk of progression and more common barriers to effective treatment

References

- The African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study (ADAGES) III: Contribution of Genotype to Glaucoma Phenotype in African Americans: Study Design and Baseline Data. Zangwill LM, Ayyagari R, Liebmann JM, et al. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):156-170.

- Latanoprost for open-angle glaucoma (UKGTS): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Garway-Heath, David F et al. The Lancet, Volume 385, Issue 9975, 1295 – 1304

- Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Gazzard, GusAmbler, Gareth et al. The Lancet, Volume 393, Issue 10180, 1505 – 1516

- Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Pivotal Trial of an Ab Interno Implanted Trabecular Micro- Bypass in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma and Cataract: Two-Year Results. Samuelson TW, Sarkisian SR Jr, Lubeck DM, et al. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(6):811-821.

- Observational Outcomes of Initial Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C in Patients of African Descent vs Patients of European Descent: Five-Year Results. Nguyen AH, Fatehi N, Romero P, et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(10):1106-1113.

- Ahmed Glaucoma Valve implantation in African American and white patients. Ishida K, Netland PA. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(6):800-806. doi:10.1001/archopht.124.6.80

Latest Articles

HCP Popup

Are you a healthcare or eye care professional?

The information contained on this website is provided exclusively for healthcare and eye care professionals and is not intended for patients.

Click ‘Yes’ below to confirm that you are a healthcare professional and agree to the terms of use.

If you select ‘No’, you will be redirected to scopeeyecare.com

This will close in 0 seconds